Lucha libre stadiums across El Paso, Texas and Ciudad Juarez, Mexico region fill with thousands of eager fans every showing. Its rich history saturates itself across the bi-national community as it has brought people together for almost a century.

Lucha libre is Spanish for “freestyle wrestling.” It has a history in its transcendence through the southern U.S.-Mexico border with El Paso as its place of origin beginning in the 1930s. Freestyle wrestling had already been a prominent form of entertainment in the El Paso region during the Mexican Revolution when Salvador González, who fought in the revolution, attended a match and found so much interest in it that he took it back home to Mexico City, according to Texas Highways.

González founded Empresa Mexicana de Lucha Libre making him the “Father of Lucha Libre.” The sport expanded and grew in popularity across borders, making it a form of connection between cities, people and cultures.

The lucha libra industry in El Paso had a steady progression and brought up wrestling stars throughout the decades that are native to the region such as The Guerreros and Cinta de Oro. Wrestlers such as Eddie and Chavo Guerrero joined the top dog of wrestling in 2000 when they were introduced into Worldwide Wrestling Entertainment (WWE). Cinta de Oro joined later in 2011.

On the other side of the border, Ciudad Juarez also has its variety of stars and shows, like Pagano and Cassandro who are luchadores in Lucha Libre AAA. Pagano made his debut in 2008 and is still kicking it hard in the ring. Cassandro, who made his debut in 1988, had an abrupt stop to his career after suffering a stroke in 2021.

As the years pass lucha in La Frontera doesn’t only make a name for itself through its selection of successful wrestlers, but it also serves as a cultural connection between both nations, families and friends.

Owner of El Paso’s Lucha League Wrestling, Karina Hernandez has been running the independent wrestling company since 2020. The company was built from the ground up with the help of lucha league wrestlers, family and other companies in El Paso.

“Every time we have a wrestling show, or we connect with somebody it’s funny because [lucha] is one of those things where people come and tell you, ‘When I was little my grandma, my grandpa, my dad used to take me to the luchas in Juarez and the ones here,’” Hernandez said. Hernandez noticed that when Lucha League made its mark in 2020, other companies started establishing themselves from the ground up in El Paso – making for a growing lucha community in recent years. She said at the start of their company they only had two or three competitors, but El Paso now has about seven other companies throughout.

“I think here in the community, especially because we’re Mexican American… there’s a very thin line where you could split the cultures. We’re very Mexican, and we’re very American. It’s part of our culture whether you like it or not,” Hernandez said.

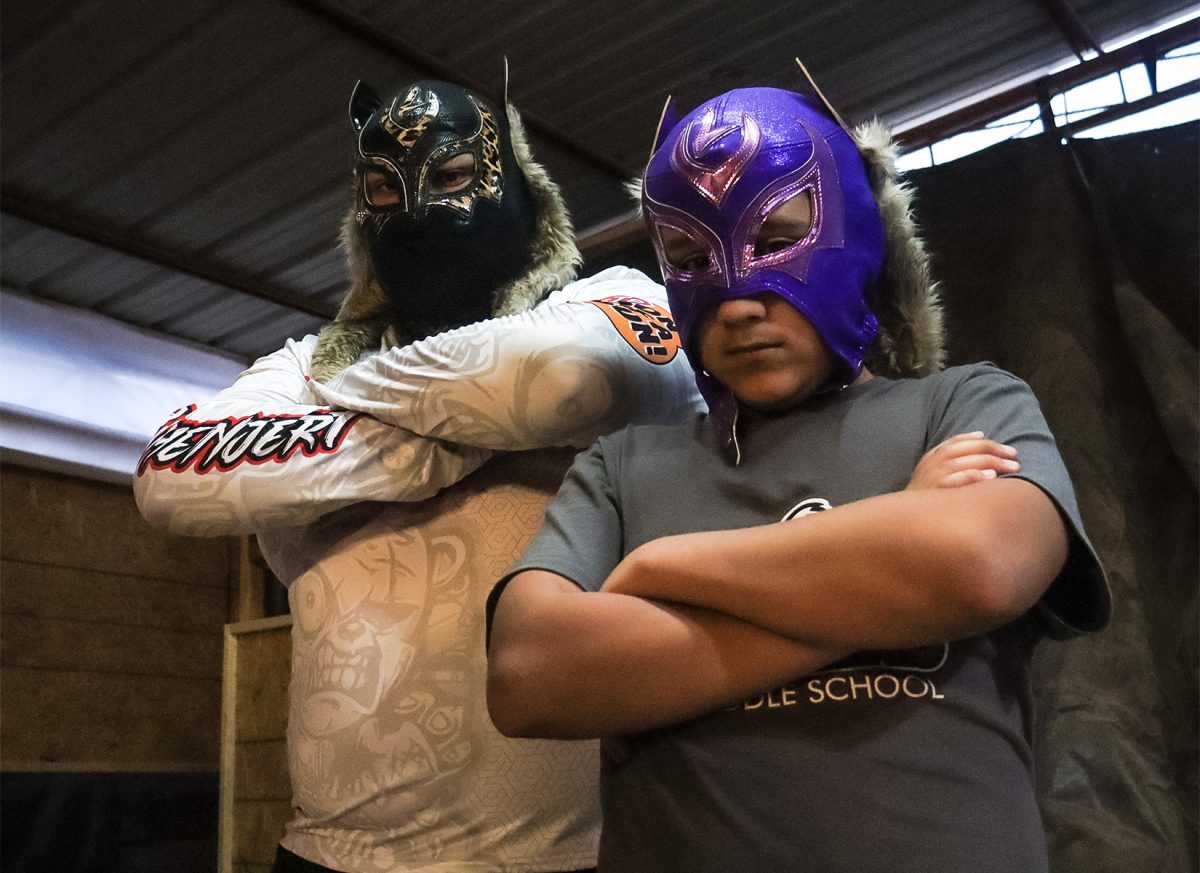

The recently founded El Paso wrestling companies are all considered “indie companies” that support independent wrestlers without binding contracts to uphold. These wrestlers include Lucha League’s tag team, the “Lobros,” made up of retired MMA fighter and luchador of 16 years, Lobo Díaz, and his 13-year-old son Lobito Díaz who has been practicing lucha libra for the past four years.

“[Lucha] is our version of a canvas,” Lobo said. “We’re the paintbrush. An artist comes and paints his masterpiece and that’s kind of who we are. We wow the crowd with different moves it’s pretty cool to see.”

The Lobros have been painting the community with entertainment, but also connectedness. They hope that the future of lucha libre and wrestling in El Paso includes further education on lucha libre’s roots and use it to further enrich the community.

Lucha League has made its contributions by providing literacy programs through their comic books at the local libraries and hope to get started on a project called “The Luchabus.” In the parking lot of Lucha League’s ring sits an old bus that will soon be turned into a like-new mobile lucha museum.

“There’s a lot of history that has gotten forgotten that we need to restore,” Lobo said. “If we can [use] the bus to show that history–it’s a cool way to take this history to somebody.”

The future of lucha libre in El Paso has the potential to become educational and teach about the rich history of lucha on the border, as well as continue to tie communities together the way the sport has done so before.

Jesie Garcia is a staff reporter and may be reached at [email protected] or on Instagram at @empanaditawrites.