As President Donald J. Trump’s increased immigration policies and executive orders effect borders nation-wide, the big switch to more strict enforcement creates room for confusion on what orders may mean.

As a border university, The University of Texas at El Paso (UTEP), provides education to an 84% Hispanic population. With the challenges facing the border, knowing what rights a person has is vital.

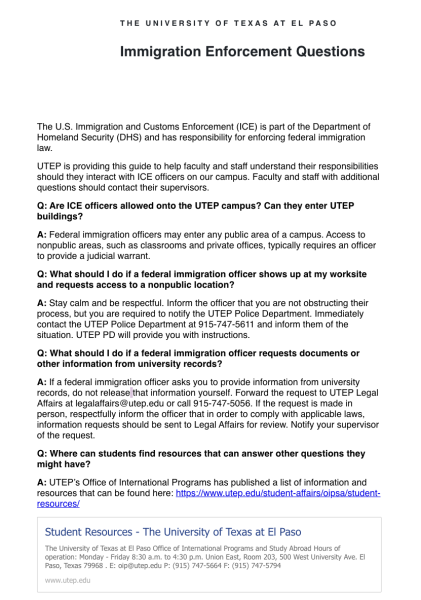

On Feb. 3, UTEP sent a memo to their staff in response to information of potential U.S Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) raids on campus.

The memo stated, “federal immigration officers may enter any public area of a campus. Access to non-public areas, such as classrooms and private offices, typically requires an officer to provide a judicial warrant.”

ICE or U.S Customs and Border Protection (CBP) can have judicial or administrative warrants. A judicial warrant, according to the National Immigration Law Center, is “formal written order issued by a judicial court authorizing a law enforcement officer to make an arrest, a seizure, or a search.” Whereas an administrative warrant does not allow law enforcement to conduct a search of a persons but still allows arrests and seizures. Additionally, an administrative warrant is issued by federal agencies, potentially through an ICE agent or Department of Homeland Security officer.

It is vital that people in the U.S remember their rights if they come in contact with an immigration officer. The fourth amendment prohibits unreasonable searches and seizures, meaning that unless police have probable cause or reasonable suspicion to search a person, law enforcement would need a warrant.

The memo informed staff to contact campus police immediately in the event of a situation, and that all documents and other information be provided to officers only through UTEP’s legal affairs department.

People may have questions about what a situation like this could look like if it were to play-out. Immigration lawyer Gabriel Jimenez has 25 years of experience in immigration and nationality law.

“A good way of thinking about it is, whatever the campus police can do or can’t do, the same rights and obligation would apply to ICE,” Jimenez said. “Anybody who is here in the United States–it doesn’t matter what their immigration status is, has the same rights in the constitution a citizen has.”

The 1969 Supreme Court case, Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District declared that “students do not leave their rights at the schoolhouse gates.”

“Even if you’re on school grounds you still have all the constitutional protections there are in schools, you [students and faculty] have the right to remain silent. You don’t have to answer their questions,” Jimenez said.

The process of being detained by a police officer and an ICE agent are similar as they both provide the right to remain silent, right to an attorney or consulate, and right to deny signing or saying anything by invoking the Fifth Amendment.

However, when it comes to immigration cases, the government is not required to provide a lawyer. Instead, a list of free or low-cost alternatives may be provided if requested.

Jimenez suggests that students and faculty collaborate with each other in creating presentations or handouts to inform others on their rights and to contact those well-versed in immigration law if they need more information.

UTEP has resources such as the Office of Counseling and Psychological Services.

Texas Rising is a Texas-based non-profit organization focused on social justice. Residing in a border city, the UTEP chapter of the organization has first-hand experience in this crisis.

“It is the university’s responsibility to protect all students on campus. College campuses should be spaces for learning, not enforcement operations. Every student deserves the right to pursue their education without fear of federal agencies like ICE disrupting their learning environment,” Texas Rising said.

If students want to remain informed and push for stronger protections Texas Rising encourages students to contribute and become part of the solution.

“Join organizations already doing the work, movements need people, and by becoming part of these efforts, you can help build a stronger community. Contacting representatives, attending hearings and mobilizing peers can directly influence policies that will impact our community,” Texas Rising said.

Vianah Vasquez is a writer contributor and may be reached at [email protected].