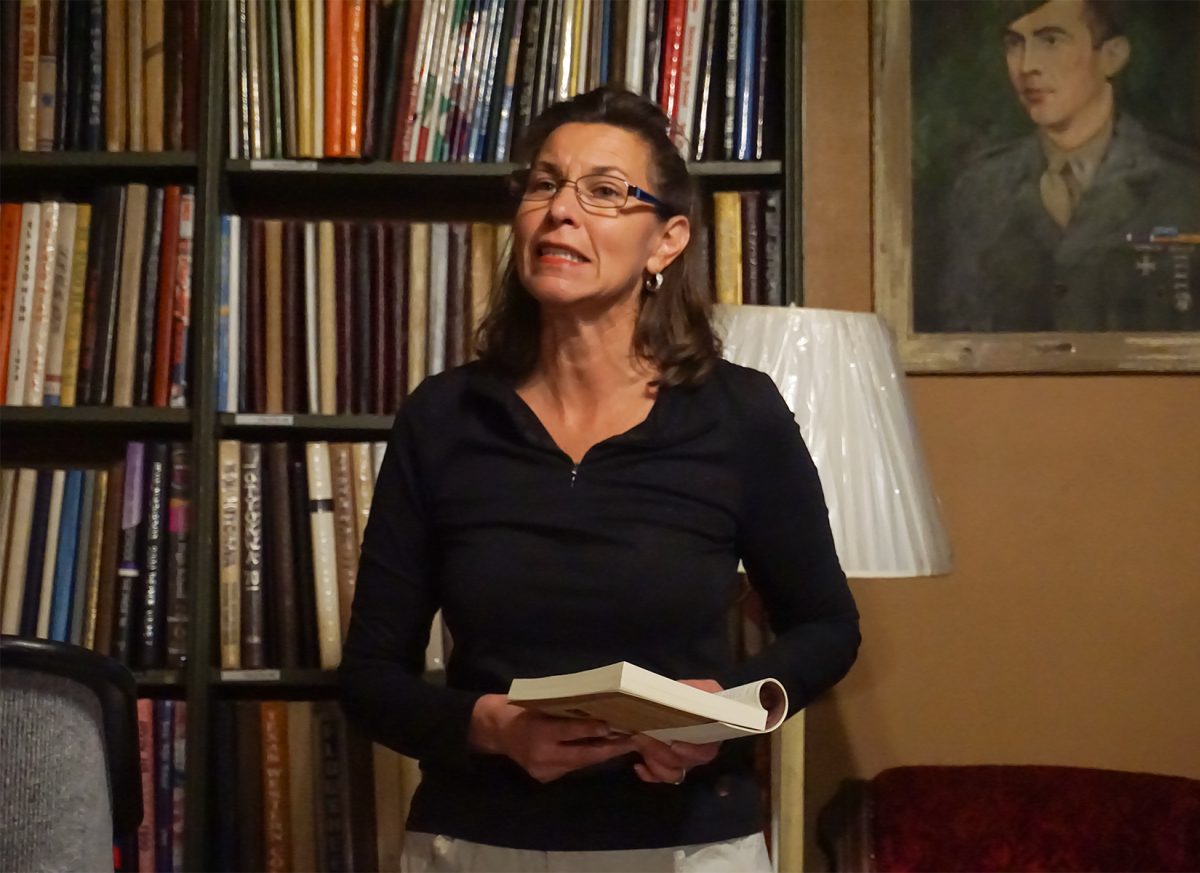

When researching soldaderas, female Mexican soldiers, for a potential novel, Cristina Ramirez, Ph.D., said she found close to nothing. Finding a lack of female Mexican American history pushed Ramirez deep into the research she’s now dedicated to.

The intent of Ramirez’s research is to find and uplift female Mexican history that has been overlooked or lost.

“I realized that there was a gap of information—a gap of students being able to see themselves in the literature that they were reading,” Ramirez said. “Especially young women.”

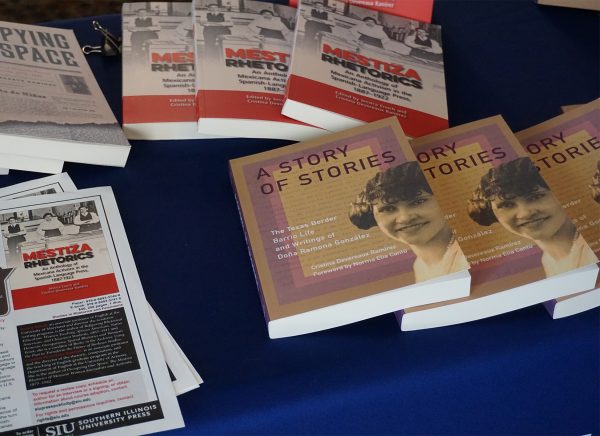

Ramirez’s first and second books, “Occupying Our Space” and “Mestiza Rhetorics,” are bilingual anthologies of lost writings by Mexican women. She said their stories were found through trips to Durango, Guanajuato and Mexico City, as well as searching on digital archives. Then, the old discovered literature is then revived by Ramirez through the use of modern-day technology.

“What I had to do was get [these] texts, transcribe it into a manipulatable word document, and it had to be accurate. Extremely accurate,” Ramirez said. “I have dedicated myself as a scholar to this work.”

Ramirez’s mother called her, frantic, one evening during her Ph.D. research.

“[My mom] says, ‘You need to get over here now… we have your grandmother’s writings’,” Ramirez said.

Ramirez’s grandmother, Doña Ramona Gonzalez, was a storyteller from the Chihuahuita neighborhood in south El Paso. She published short stories alongside Chicano literary giants like Rodolfo Anaya and Tomas Rivera, competing for the Quito Sol Award, a respected award for Chicano writers.

“My grandmother didn’t win [the award],” Ramirez said. “Her voice was kind of deferred. Her dream remained deferred.”

The writings in the old cardboard box that Ramirez’s mother had found were much more than Gonzalez’s published work.

“What was in that box was over 750 pages of my grandmother’s manuscript-ready writing, unpublished,” Ramirez said. “[My family said], ‘What are we going to do with all these writings?’ I said to give it to me. I know exactly what to do with these writings. And at that moment… I knew my grandmother was speaking to me.”

Ramirez said she felt as if this was a box of unanswered questions.

“The grief that I had before finding these writings, and even after, was not speaking to her and asking her questions [about her history],” Ramirez said.

As Ramirez let Grandma’s old writings transform her grief, she took a scholarly approach and started finding the historical contexts to every piece of writing.

“I started framing the history around the Chicano literary movement, and then more around the El Paso history, and that’s what really took me so much time to write this book.”

From there, her book “A Story of Stories: The Texas Border Barrio Life and Writings of Doña Ramona González” was born.

“Women write and tell different stories [than men],” Ramirez said. “They tell stories of the home, the heart, the kitchen, and that’s where our foundation comes from. Recovering these stories… it’s enhancing the history that we have. I feel like there’s not enough of an emphasis put on what was going on at home. What was going on with the normal people?”

Grandma Gonzalez’s stories are not focused on the bigger picture of history but share stories of colloquial life in the barrio.

“History tells us who we are,” Ramirez said. “When you have a lack of representation in Chicano and Mexican American history, it’s almost a way of erasing us. It’s a way of showing that we are not capable of making history. The reason that recovering this kind of history is important is so that young women can see themselves because that’s the power of writing.”

Jesie Garcia is staff reporter and may be reached at [email protected] or on Instagram @empanaditawrites.