Editor’s note: This article is part two of a three part series surrounding the cultural discussions around Mexican-Americans that do not speak Spanish, also known as “No Sabo” kids.

Editor’s note: This article is part two of a three-part series surrounding the cultural discussions around Mexican Americans that do not speak Spanish, also known as “No Sabo,” kids.

From one no sabo parent to a whole generation of no sabo kids; there is hope in healing and opening the doors to learning Spanish whenever the time comes. Instead of being fearful or timid around language, there comes a pivot where one becomes eager to learn what is next for language.

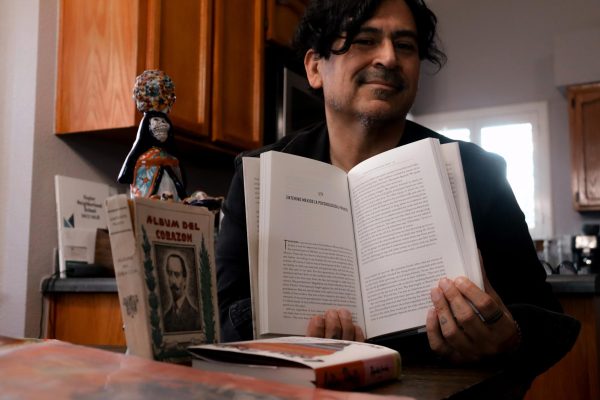

Tim Hernandez, Associate Professor at UTEP, a published writer and author, speaks up on the phenomenon of being a “no sabo”. His relationship with Spanish is a curious one.

“Growing up, it was only the adults around me that spoke Spanish, and Spanish was a language where us younger kids weren’t allowed to be inside of that conversation that the adults were having,” said Hernadez. Spanish was always at arm’s reach. “My parents spoke Spanish whenever they didn’t want us to know what they were talking about. So, it was used as secrecy. That also taught us something as kids growing up in terms of that, that language wasn’t for us.”

Hernandez sympathizes and gives grace to all no sabo kids, because he endured the same ridicule that came from the older generations when he was growing up. “I was raised with the other side, the old school way of our elders or the adults around us kids made us feel bad they didn’t teach us Spanish,” said Hernandez.

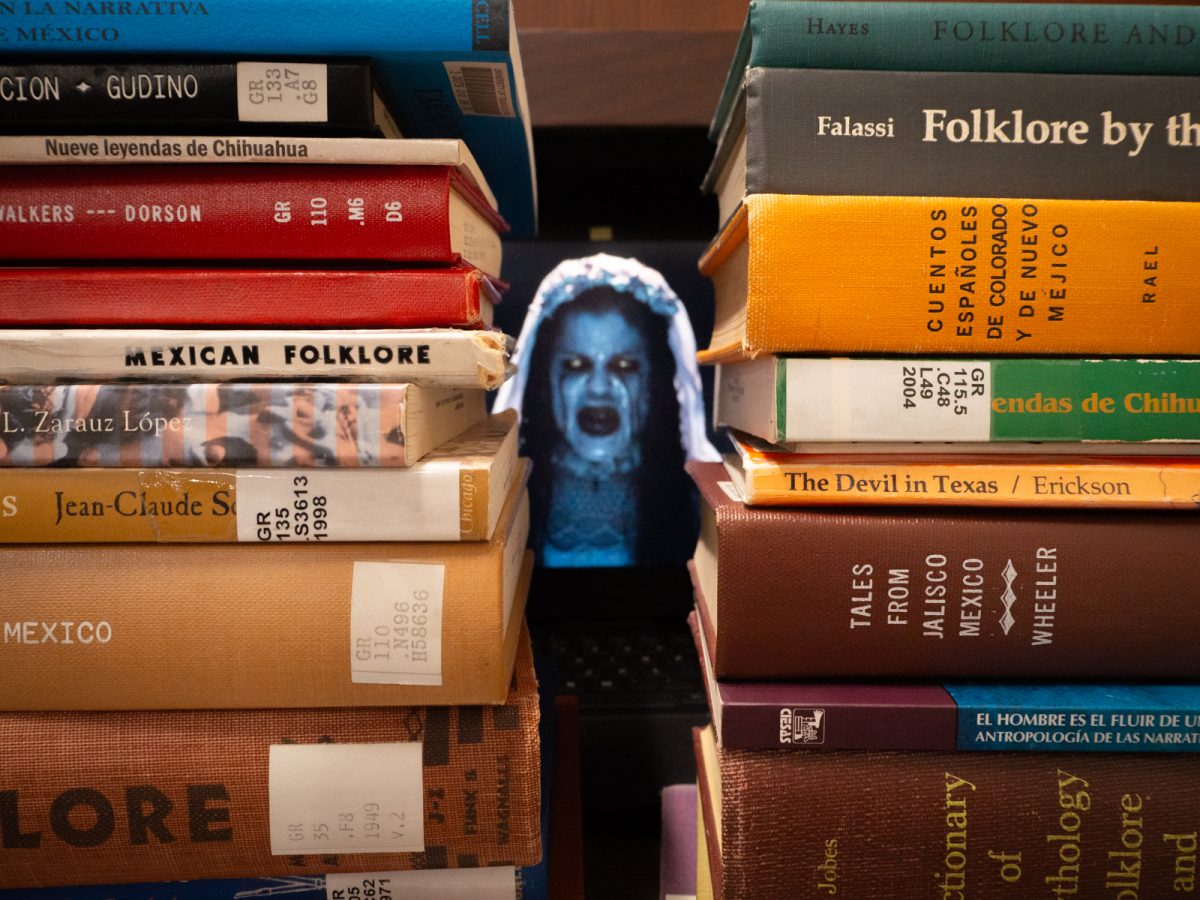

Something to remember and reflect on is that the Spanish language carries a lot of trauma and generational pain. From the shores of Veracruz to generations that endured the swatting culture in the 60s.

“What happens over time is you’re literally having the culture beat out of you,” said Hernandez.

There were no expectations in his household raising his children that they must know Spanish. On the contrary, he had other ideals.

“I wanted my children to master the English language. I want them to become masters of this world that they’re in, you know, or at least in this particular country, and the reality that they have to navigate every day, which is here in the United States,” said Hernandez.

Perhaps the reason why no sabo kids are merging into this country, not with their tales in between their legs, but with pride—to be able to speak fluent English, is because of their ability to choose, something generations before did not have.

“I think we’re (no sabo kids) the redemption that our grandparents were seeking,” said Hernandez.

What he says to other no sabo kids like himself and his kids is that they should not be ashamed.

“There’s no nothing to be ashamed of inside of that not understanding or speaking language when that wasn’t your reality or what you grew up in,” said Hernandez. “It’s sad that some parts of our community want the other parts to feel ashamed for that, or to feel or to be made to feel bad about the fact that they don’t speak Spanish. It’s sad because it’s negating who they are as a human being on their own,” said Hernadez.

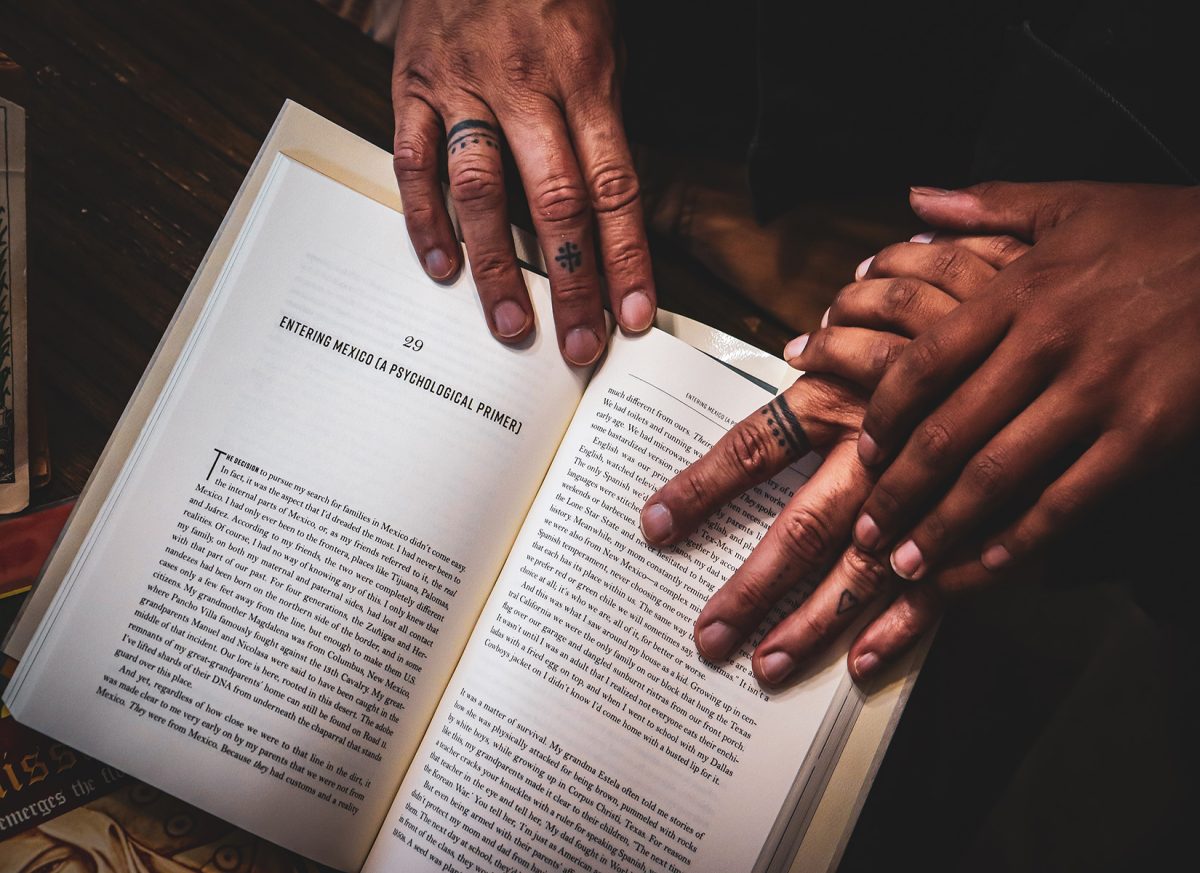

The ironic dynamic that the ones who ridicule the no sabo kids are the people that are monolingual in Spanish only. The ultimate peace that the no sabo kids could eventually face is healing from the resentment and burden of not being fluent. Hernandez rooted back into his learning journey recently when his books made him go into Mexico despite years of despising Spanish.

“It wasn’t until I moved away from home, when I got far away from that community, where I was in a place where I could hear myself thinking and my own voice…it took 10 years for me to come back around and realize that it was very practical to learn Spanish,” said Hernandez.

Once his doors became more open to the idea of healing and jumping back into his cultural roots and tapping into that identity, he discovered new realms of being no sabo.

“I started to feel a part of me awaken that I had not known that was even asleep…it made me want to go into Mexico, with my messed up Spanish without a translator, I am just going to throw myself in there, cause I think I have what it takes to at least get through,” said Hernandez.

After taking that leap of faith, the world started to seep colors back into his world. “Now every time I go to Mexico, I make it intentional to go without any translation. I let myself ‘fail’ because the situation will correct me, I come out of it with a better understanding of myself,” said Hernandez.

The more healing no sabo kids do with their cultural identity, the more it gives back to generations that came before them.

Dominique Macias is a staff photographer and may be reached at [email protected]