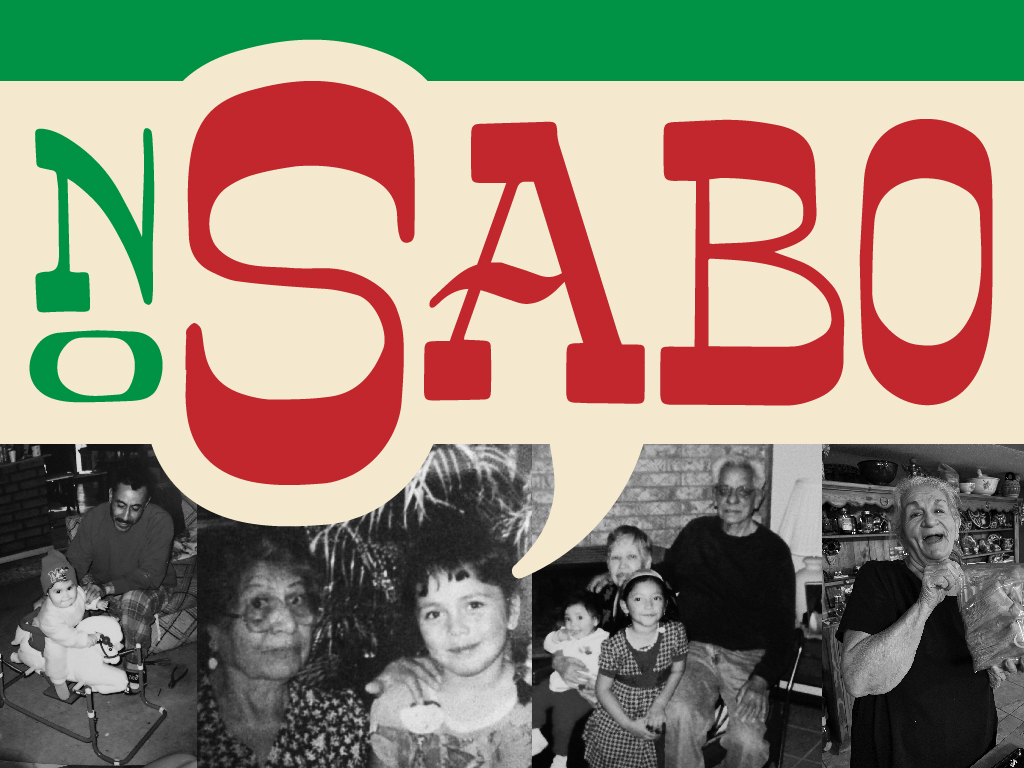

Editor’s note: This article is part one of a three part series surrounding the cultural discussions around Mexican-Americans that do not speak Spanish, also known as “No Sabo” kids.

Either a Hispanic person is bilingual, in a binational city or are classified as a “no sabo kid.” It’s a frustration only a few people will understand. However, the older generation has a lot of feelings toward the younger generation, not being fluent in Spanish. Turns out, they fall under the same grey area.

For a better understanding, there’s a scene in the 1997 movie, “Selena” where Abraham Quintilla explains to Selena and her brother, “you have to be twice as perfect.”

Selena’s father points out that Selena, originally a ‘no sabo’ kid herself, can sing in Spanish perfectly, but when she speaks it, it will not be accepted by other Mexicans. He goes along saying how exhausting it is to constantly prove to the Americans how “American” they are, and how “Mexican” they are to the Mexicans.

“Our homeland is right next door, being Mexican-American is tough. Anglo’s jump all over you if you don’t speak English perfectly, Mexicans jump all over you if you don’t speak Spanish perfectly.”

The older generation of son Sergio Del Val, 77 and mother, Gloria Del Val, 98, share their input on how discouraging it was to learn English and get ridiculed. Gloria Del Val’s first language is Spanish, and she tells the story of how critical the Americans acted toward her for learning English.

She got to the United States from Veracruz, Mexico in 1952 and her relationship with the English language was short spanned.

“I started taking classes soon after arriving in the states, but I quit very quickly. I got made fun of, they called me dumb, for the way I spoke English,” said Del Val.

Her son stepped in and told his tale on how he was a part of the infamous swatting culture in schools in the late 50’s.

“It was pretty common back then. The teachers and coaches would compete with who had the best swatting paddle. So, they had one pedal with holes in it,” said Sergio Del Val.

Sergio Del Val’s first language was Spanish as well, taught by his parents. His native tongue did not veer away from his upbringing with the punishment.

“I did lean more toward English in school,” said Del Val. “But at home, I had to speak Spanish.”

Del Val recalls that he and his peers took swatting as a game.

“We would speak Spanish and then see if they would catch us,” said Del Val. “We all took it as a joke.”

Swatting culture stopped in the mid 1960s when Del Val was in high school.

Gloria Del Val shares how defeated she feels about not being able to speak to her grandchildren and the younger generations of her family because of the barrier.

“It (language) is everything to me,” said Del Val. “I want to say certain things to the kids and express myself, but I can’t because they can’t understand me.”

Her son sympathizes on account of his mother and explains how during family reunions, everyone is speaking both Spanish and English, but more so English, and she becomes very distant and there is a divide.

As to the reasons why fewer families seem to teach the younger generations Spanish, Sergio Del Val, says that he tried to teach his kids Spanish. However, the discouragement and criticism made his kids not stick to it as prominently as he did growing up.

“What happens is that, when one of my kids would say something wrong in Spanish, others would laugh at them, so they did not want anything to do with that anymore,” said Del Val.

He also connected his experiences with his wife’s and her relationship with the Spanish language growing up in the 60’s.

“She was also punished for speaking Spanish,” said Del Val. “It was nothing but English from that point on, and she lost all her Spanish, really. So, when my kids grew up, their mom didn’t want them to learn Spanish because she didn’t want them to have a Mexican accent.”

With that lesson of life, Sergio Del Val, understands that the lack of learning Spanish for the younger generations was inevitable.

“I think it’s so prevalent now that people are not fluent. It may not be as needed anymore as it was in the past… I can sympathize because I have been there.”

Gloria Del Val had a bittersweet response to say, when asked if she gives grace to the no sabo kids.

“Yes, I feel for them, but they should know their language that is a part of (them). They should be proud of being Mexicans.”

Dominique Macias is a staff photographer and may be reached at [email protected]