We all may have a friend or family member in our lives that when it comes to what we wear in our daily lives, can easily put our casual outfits to shame. Every decade in fashion is interesting, from the colorful tie-dyed shirts of the ‘60s to the punk rock flannels of the ‘90s.

One name familiar to those interested in fashion history is Mansor Farah. Farah, a Lebanese immigrant who sold dry goods and hay, traveled from Canada to El Paso, Texas. He, along with his wife Hanna Farah, had one goal in mind, to make their mark on making clothes in America.

Farah’s extended family eventually started to take over a highly popular company expanding rapidly in production after Farah’s death in 1937. Farah’s two sons took the reins, with eldest son James Farah taking over administrative duties and youngest son William Farah taking over production duties. Each year the company grew increasingly to the point of becoming a brand-name wholesaler and manufacturer in the mid-’60s.

The company then hit their magnum-opus with the creation of their own affordable and tough, permanent pressed slacks. At this point, the company was at the top with millions of dollars being generated and William now at the helm.

With his direction, products were selling to contractors who sold Farah jeans and slacks to more than 9,000 independent and regular department stores throughout the United States. Soon in1972 the company became the world’s largest manufacturer of men’s and boys’ slacks.

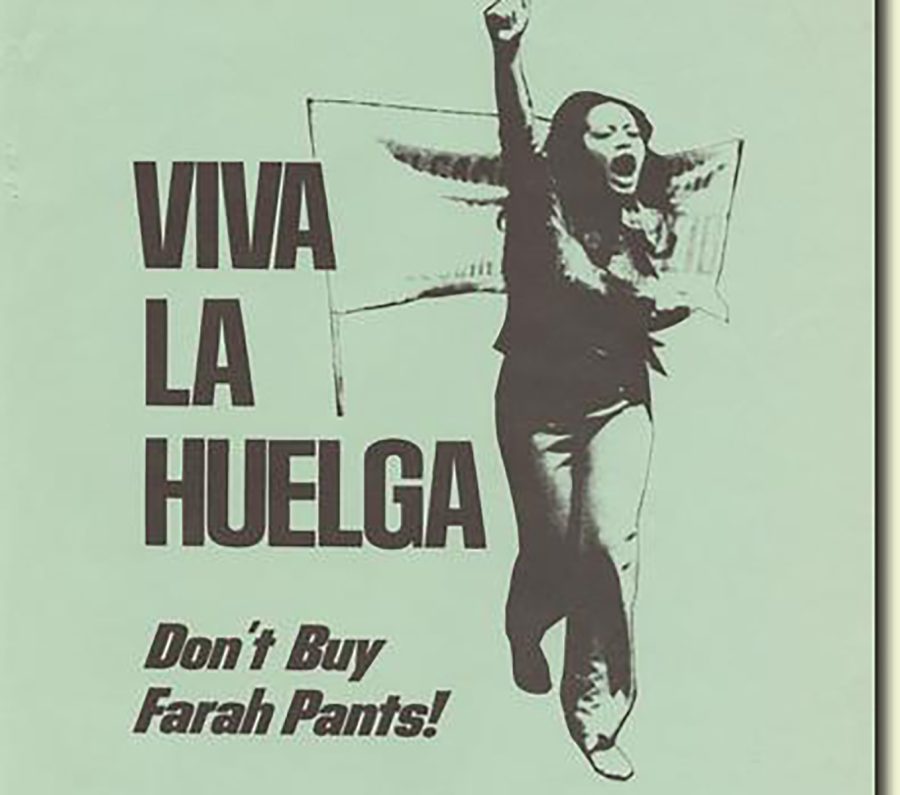

However, the curtain behind the scenes of Farah finally came down. In the spring of 1972, about 2,000 workers of the company’s seven plants went out on an enormous strike in El Paso, known as the Farah Strike.

Most of the workers were Mexican-Americans, specifically Chicana women. The strike was created to seek out higher wages, to be represented by Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America and, most importantly, have greater job security. In an article published by The New York Times (NYT) titled, “Farah Strike Has Become War of Attrition,” writer Philip Shabeoff details the event the day of June 16, 1973.

On the picket line outside the Gateway Plant, Alice Saenz, a woman who earned $1.70 an hour working in the repair room commented on the strike.

“Willie Farah paid us 10 cents an hour more than the minimum and then told us what a great guy he was,” Saenz said to the New York Times. “But the main reason we need a union is for job security. We could get fired for any reason. We didn’t have a right to say anything in the plant. When a union organizer gave me a card to read, my supervisor said, ‘You better throw it away or you’ll be fired.’”

Jose Urquizo, whose wife, mother, three sisters in law and two cousins were also on strike, said that he did not expect it to last so long when he first walked out.

“A lot of my friends are suffering. Some have had to go to Phoenix and California for work,” Jose said to NYT.

Soon after the success of the strike and support from prominent figures like Senator George Mcgovern and El Paso’s Roman Catholic Bishop, the month of July saw a nationwide boycott of all Farah Products.

The Farah Strike showed the people of the world what can happen when a group of marginalized people come together as one for the greater good. The strike was particularly inspiring in how not only a marginalized group banded together, but in how Chicana women knew their strength and worth in a work environment and fought for the right to be treated equally.

H. Catching Marginot is a contributor and may be reached at [email protected].