The nature of multi-level marketing (MLM) often gets legitimate MLM companies confused for illegal pyramid schemes, but there is a clear line dividing both concepts.

Fernando Jimenez-Arevalo, UTEP associate professor of marketing and management, said the economic MLM concept emphasizes reselling.

“Multi-level marketing is when a company sells their products to people who can also resell those same products to other people,” Jimenez said.

He said to think of it as selling small quantities of stock to one individual, rather than large quantities to corporations such as Walmart or Costco.

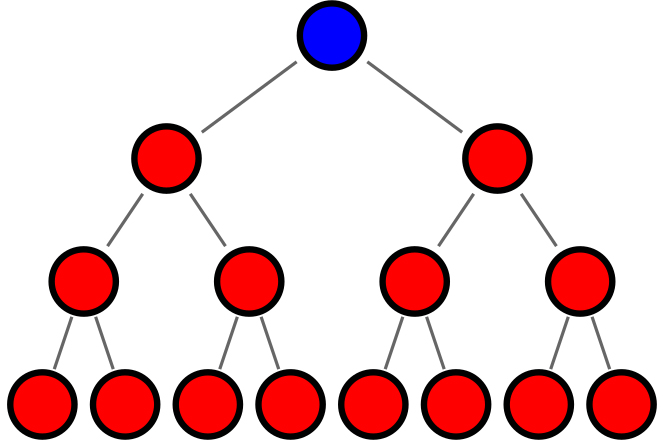

In MLM, successful individual sellers make profits through commission, a percentage of money from each sale they make. They are also able to earn additional commission by recruiting other sellers who recruit more people themselves, thus creating a profitable network of sellers.

The more sellers that they have working below them, the more commission the individual will earn. As the chain continues, the visual diagram of this strategy begins to resemble — you guessed it — a pyramid.

This raises two questions: what makes an MLM different from a pyramid scheme? and why is one legal while the other isn’t? The main difference is that an MLM actually sells a tangible product, while a pyramid scheme does not.

In a pyramid scheme, Jimenez says you start by paying an initial joining fee, sometimes up to $500.

Sometimes sellers embroiled in pyramid schemes are required to pay an additional monthly fee on top of that. Once an unsuspecting victim joins a pyramid scheme, their instructions are to recruit more and more people, eventually resembling a pyramid structure of sellers.

Recruits are told that only recruiting matters, instead of the actual product.

“Sometimes, nobody is even selling anything,” Jimenez said. “In multi-level marketing, you don’t need to recruit if you don’t want to. It is encouraged because you receive some incentive from the sales other people make, but it’s not required.”

A classic example of a pyramid scheme shut down by the government is in the case of Global Information Network (GIN). GIN branded itself as an address book full of important contacts, including some of the most elite and powerful financial experts in the country, that would help its members network and level up in their professional career. The company was founded by Kevin Trudeau, a man notorious for prior run-ins with the FTC due to his deceptive infomercials and false health claims published in his book “The Weight Loss Cure ‘They’ Don’t Want you to Know About.”

An investigation done by CNBC found that GIN was ultimately a $110 million pyramid scheme Trudeau created in order to hide his assets and evade paying more than the $37 million he owed the FTC as a result of his already established fraudulency. At its peak, GIN accumulated more than 35,000 members. Trudeau was arrested and charged in March 2014 and is currently serving a 10-year prison sentence.

El Paso Community College student Karine Irwin, 19, has been a distributor for the cosmetics company “Sengence” since January 2018.

“At first I tried to sell. I never really tried to recruit,” Irwin said. “They like you to recruit because you get commissions, but I have a great paying job as a waitress, so I never really considered this a career opportunity.”

Despite earning no extra commission, Irwin reported an average profit of $300 for every $600 in orders she placed. She described an overall positive experience working with the company, especially as an avid fan of makeup.

“I actually really only signed up because I loved the products and get a discount as a distributor,” Irwin laughed. “Overall, I don’t think I have any regrets. I never spent more money than I had and I made a lot of friendships through the company.”

Another multi-level company called Vector has made frequent visits to UTEP in the past. David Rodriguez is an assistant manager for the company and was stationed at a popup information booth inside the Union East building. He explained that Vector teaches its recruits basic entry-level marketing skills by providing them with a free training manual. After this, they are tasked with selling kitchenware products from a company called Cutco. Sales pitches are made on an appointment basis.

“It’s not like door-to-door cold calling,” said Rodriguez. “You set up appointments and you get paid regardless of results. It’s nothing like traditional marketing jobs,” he added.

Though this may sound appealing, Rodriguez admits to the company’s high turnover rate.

“Most of our people that come in do it for a few weeks, and then they leave,” said Rodriguez. “We don’t mind if they leave, that’s fine, but at least they were able to get those marketing skills.”

While many have taken on MLM side gigs by selling for companies like Sengence, Herbalife and Mary Kay, Jimenez discourages students from pursuing these jobs full-time. Instead, he encourages students to think practically and make wise use of their time.

“Typically, I ask my students if a certain product is good or not, why isn’t it on Walmart’s shelves? I could make much more money just by selling truckloads of this in retail stores rather than by selling it one-on-one,” Jimenez said. “Even if you’re a talented salesperson, it doesn’t make financial sense to sell one product at a time and still make a profit.”

Despite the skepticism of some multi-level business models, Jimenez says that a good way to gauge if a particular company is legitimate or not is by asking several questions.

“I would typically challenge them to give an exact amount,” Jimenez said. “How much do I need to sell or how many people do I need to recruit in order to make $1,000 a month? If they cannot answer that question, then you know it’s probably a pyramid scheme.”

Though the presence of these unorthodox business models has increased since the rise of the internet, they still only make up a fraction of retail as a whole.

“A typical misconception of salespeople is that they are shady and want to maximize their benefits at the expense of a consumer. I would say, that’s not true,” Jimenez said. “In every profession, there’s good and bad. Successful salespeople are good, honest, reliable and trustworthy. Don’t let these pyramid schemes damage the reputation of salespeople in general.”

Margaret Cataldi may be reached at [email protected]