The average college student worries about deadlines, exams, projects and all that comes along with being a student.

Many students at UTEP can maintain their standards in school on account of the privilege of living with family, roommates or a stable place to live throughout their seemingly unending college days.

But there is a small population of college students who, despite experiencing the same rigors of school as their peers, face an incessant worriment: homelessness.

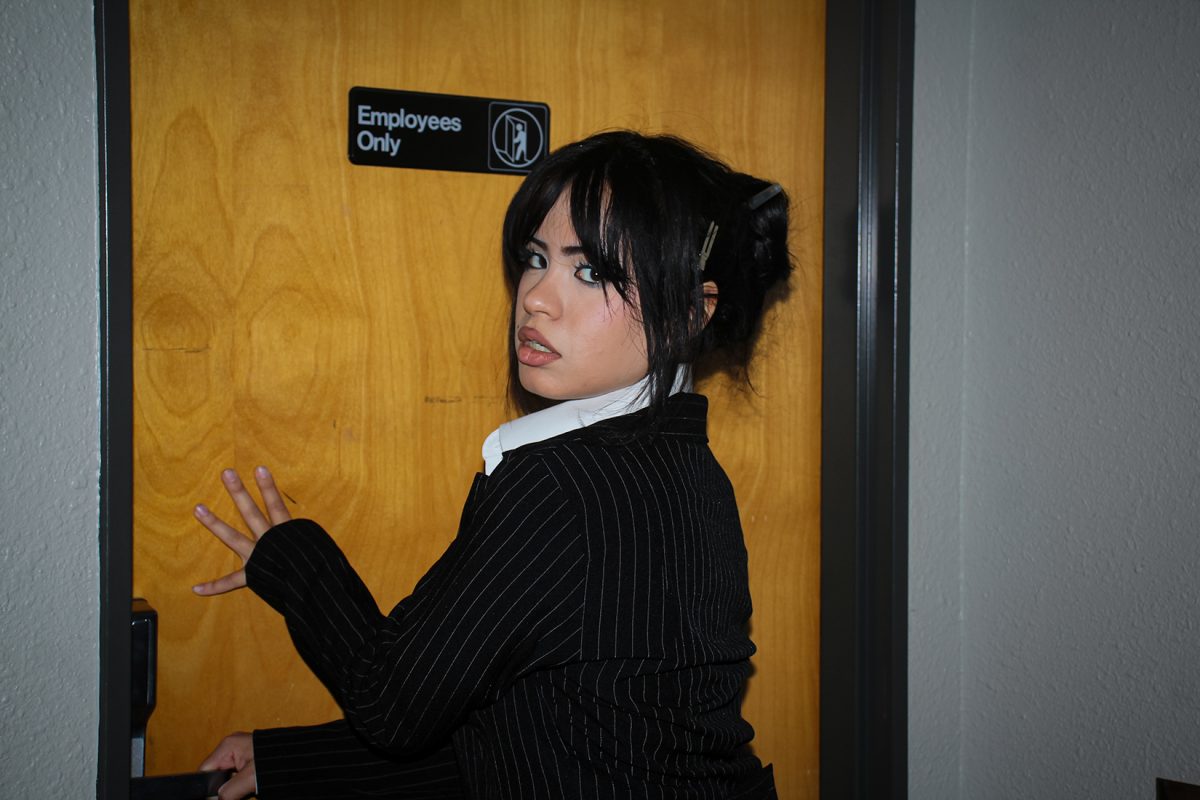

Unlike the general homeless population, it’s not easy to distinguish homeless college students from their classmates. Some bounce around from friend to friend to stay at their place for the night, while many are forced to live out of their cars. Some find refuge at shelters or motels. But when there’s no space in shelters or not enough money for both food and a motel room, homeless students have no choice but to hit the streets and survive on their own with whatever they have.

This reality is gaining more attention due to the findings of a study called “Still Hungry and Homeless in College” by Wisconsin HOPE Lab founder Sarah Goldrick-Rab and four other co-authors.

The study was HOPE Lab’s third national survey. The previous two surveys focused on community colleges, while the latest survey studied on 43,000 students at 66 institutions in 20 states and the District of Columbia. The study emphasized the prevalence of food and housing insecurity among college students. The results of the survey showed that 36 percent of university students were food insecure 30 days prior to participating in the survey and for community college students, it was 42 percent.

Regarding homelessness, 12 percent of community college students and nine percent of university students were affected in the year before. Six percent of community college students and four percent of university students had been kicked out of their homes, while four percent of community college students along with three percent of university students spent nights in places not meant for housing, such as cars or abandoned buildings.

Rescue Mission of El Paso takes in 15,000 to 25,000 people every year, but not all those people are from the Sun City. Of the people who are welcomed by the shelter, four percent of them are students.

Matt Luna, a native from Alabama was one of those students who comprised the four percent. He recalls the days in recent years when he didn’t have an assured place to stay for the night and struggled to keep up in school.

“When I first started going to Rio Grande (El Paso Community College, or EPCC), I was either sleeping at a friend’s house or renting a motel,” said the 30-year-old staff member at Rescue Mission of El Paso and EPCC student. Luna lives and works at the shelter.

After a series of momentous life decisions and instability, Luna’s circumstances eventually led to homelessness. Luna became chronically homeless at 27, causing him to drop out of school. He has worked to get back on his feet, getting himself off of drugs and alcohol.

“I was heavily involved with gangs and doing drugs and doing all that,” Luna said. “And then I became an alcoholic and I was an alcoholic for like three years, and I was homeless living on the street.”

Luna resorted to drinking when the stress of his bills, especially for college tuition, built up. He remembers losing hope of attending school because he did not have enough money to pay for tuition. But during the time that he was enrolled in school, Luna would take advantage of any opportunity he got and used it to study. It was difficult for Luna whenever he had to decide between going to work, so he could feed himself or go to school. More than once, Luna preferred to sustain himself and had to make sacrifices in order to survive. Those sacrifices included missing class.

Eventually, homelessness was what caused Luna to drop out. Luna made the decision to stop drinking and got sober. To avoid picking up the habit again, he resorted to Rescue Mission of El Paso, which he now depends on for his source of income and a stable place to stay. With the support of the shelter, Luna was able to return to EPCC.

“Now that I’m kind of steady here (Rescue Mission of El Paso), I pass the class, it brings up my GPA a little bit,” Luna said. “And this is the last class I have to pay for before I get financial aid.”

El Paso Community College campuses do not offer a special housing support for students in homeless circumstances, except the Valle Verde campus, where last year EPCC’s Student Government Association began running a food pantry to all students that are food insecure. However, the community college offers to counsel students on the brink of a personal crisis. As soon as Luna earns his associate degree in social work, he hopes to transfer to UTEP.

At the public university level, there are more sophisticated initiatives aimed to help homeless students. UTEP’s Foster Homeless Adopted Resources (FHAR) program aims to connect foster, homeless and adopted students with resources to help them advance through their college career.

According to UTEP Communications, anywhere from 80 to 120 students enter the program each semester. The program alleviates homeless students or students on the brink of homelessness with necessities, including hygiene and household supplies, a food pantry, bus passes, access to housing—as FHAR has a partnership with UTEP Housing and Residence Life—and centrally, access to education.

Director of the FHAR program, Pat Caro, told UTEP Communications earlier this year that if any UTEP undergraduate or graduate student “who finds themselves in a situation where they are homeless or adopted, or fostered and they need help, can come here (FHAR) and we can point them in the right direction and we’ll assist them.”

Students qualify for the FHAR program if they share housing as a cause of economic hardship or loss of housing.

For more information, call the FHAR hotline at 915-747-5290.