After J. Cole released “2014 Forest Hills Drive” to end 2014, the hip-hop nation thought the world of J. Cole and his day-one loyals put him on a pedestal, along with Kendrick Lamar and Drake, for the best rappers in the hip-hop world.

It seemed fitting for the North Carolina rapper that earned his clout through his “Friday Night Lights” mixtape and reeled in worldwide fame off his illustrious single “Work Out” in 2011.

So rightfully so, expectations were high for J. Cole in the hip-hop game, which ultimately doomed him on back-to-back-to-back studio releases. “4 Your Eyez Only” was Cole’s 2016 project that was undersold and simply forgettable, aside to a handful of catchy tracks and chart-topping, mainstream hits. The hip-hop nation simply was tired of hearing Cole talk about folding clothes and kissing women. It was just boring rap, frankly.

As Cole grew his loyal fandom through the years, so did the cult following of religious haters toward his music. You either loved his music or hated it, and anything in between felt like a shrugged “meh” response.

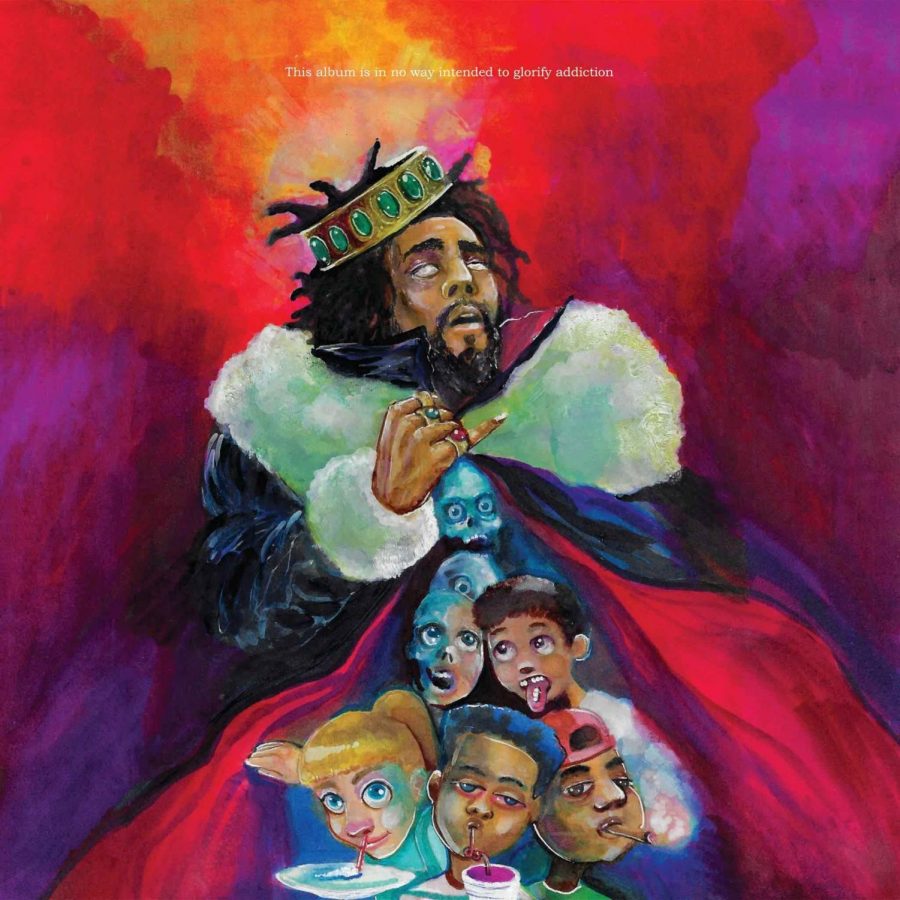

Nonetheless, 2018 was starving for a hit hip-hop album, in a year dominated by sharp indie re-emergence through an underwhelming hip-hop presence. So the naysayers and the die-hards made sure to tune in for “KOD,” J. Cole’s fifth studio album.

The title has three different meanings: “Kids On Drugs,” “King OverDosed” and “Kill Our Demons.” So, everyone expected a pseudo-deep, intellectual insight on vices that plague our society.

His fans loved it, immediately making “KOD” the best Spotify-streamed album to date and recorded 64.5 million streams on Apple Music in a day. But if this is what the modern-day rap afficianto calls “deep,” then rappers like XXTENTACION and Rich The Kid are iconic and legendary, which isn’t the case.

“KOD” falls short on reaching any sort of intellectual brand, relying on simplistic lyrics, cheesy hooks and relies on his die-hards to reaffirm that he still makes good music. Unbeknown to the album’s meaning, the tracks depict the culture surrounding narcotics, which he follows: “I’m aggravated without it. My saddest days are without it,” as he raps on “Friends.”

The recent rap culture under mumble rap glorifies extremely addictive drugs, such as Xanax, Percocets and Promethazine. It hits home for Cole as he breaks down his mother’s drug addiction on “Once an Addict,” spitting, “She kill a whole bottle of some cheap chardonnay. I gotta leave this house ’cause part of me dies when I see her like this.”

These are the high points of the album. He engraves his point by telling stories on being around drugs his entire life and the burden it leaves on him. Advocating for drug reform is something not many rappers do today, which he decides to tackle, even when it sounds corny.

Bravo, Cole, you saved the world’s drug problem.

Among some decent storytelling on the album, Cole falls short to keep the listener intrigued. The album isn’t consistent, doesn’t flow from one track to the next and sounds like a collection of thoughts instead of a cohesive album.

He sways to talking about the negative relationship experiences people face when factoring online technology on “Photograph.” Then, he goes off on some conspiracy theory tangent, speaking out against politicians and government tax money usage on “BRACKETS.” He picks up his storytelling late on the album in “Window Pain,” where he tells the story about a girl that watched her cousin get shot.

A mysterious persona, kiLL edward, appears twice on the album in “The Cut Off” and “FRIENDS.” Cole is known for gloating that he doesn’t use any features on his studio albums, which his die hards will remind you of his platinum accolades without a feature. So it’s no surprise when it turns out kiLL edward is actually Cole’s voice slowed down and low pitch on both tracks. “How come you won’t get a few features? I think you should? How ’bout I don’t? … How ’bout you listen and never forget?” he, or kiLL edward, raps on “FRIENDS.” Evidently, Cole is saying here that he doesn’t need any help to gain support on his album, which is about as anticlimactic as Logic reminding his listeners that he’s biracial.

Then comes Cole versus mainstream trap. First off, his tracks like “Photograph,” “ATM” and “Motiv8” all use trap-rap influences, which sound entirely fabricated. To close out the album on “1985 – Intro to ‘The Fall Off,’” Cole takes subliminal shots at up-and-coming rappers, possibly jabbing at Lil Pump, Smokepurpp, Lil Yachty or Lil Uzi Vert. He says he knows where they come from because he was there, but goes back and raps, “I respect the struggle but you all frontin’ these days. Man, they barely old enough to drive. To tell them what they should do, who the fuck am I?” It doesn’t solve anything and instead makes it seem like a disconnect among Cole and new rappers, whether they be good or bad.

Who knows, maybe J. Cole will come back after this and make a chart-topper. Maybe Cole fizzes out to round out the 2010s and becomes a greatest-hits touring rapper come the ‘20s. One thing is for sure, Cole is still atop the rap game in terms of popularity. Hip-hop fans just need to hold rap to a higher standard at this point.