When people ask Kenneth Chacón why he still dresses like a cholo—a Chicano with a bald head and tattoos—as a tenured professor, he tells them, “when a homeboy or a homegirl walks into my classroom, I want to say, ‘Ora, cholos welcome.’”

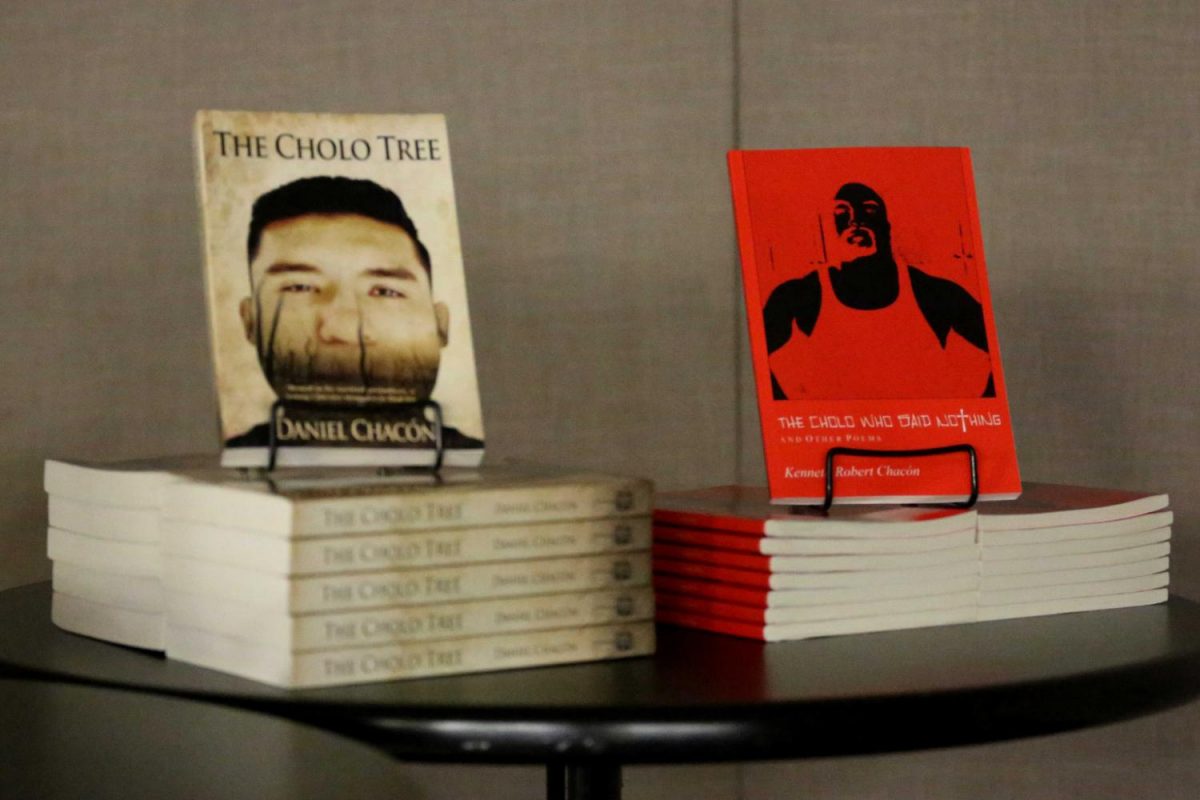

“No Cholos Allowed: A Reading and Discussion on Cholos & Pachucos,” featured two brothers and writers from Fresno, California, Daniel Chacón, chair of creative writing at UTEP, and Kenneth Chacón, chair of the English Department in Fresno City College. A reading in honor of the book’s release was held at the Tomás Rivera Conference Center on Sept. 22.

The brothers were estranged for years, and during this time, neither of them knew they were writing.

When they reconciled, they discovered they were both coming out with a book with the word cholo in the title in the same month. Daniel’s book is “The Cholo Tree” and Kenneth’s first published book is a collection of poetry called “The Cholo Who Said Nothing.”

“It’s not only interesting that we both decided to come out with books with cholo in the title and on some level deal with characters as cholos, but also that we’re writing about cholos in the first place,” Daniel said. “Because the fact is Chicano literature, Latino literature, is in a place where nobody writes about cholos anymore, nobody cares about cholos anymore, nobody wants to represent Chicanos through a cholo.”

Daniel’s novel, “The Cholo Tree,” is about an artist frequently mistaken for a cholo. Victor doesn’t think of himself as a cholo, though his mom thinks otherwise, and eventually finds himself drawn into the culture, partly because everyone thinks he already is one.

“‘I’m not a cholo,’ I repeated,” Daniel writes in his book. “More for me than for her, because I knew she wasn’t listening to me. I started to wonder why so many adults thought I was a thug, which is what she had meant, by a cholo.”

Daniel told a story of himself during high school, where, still insecure, he rode in a car with some real cholos on the way to lunch. This was his inspiration for Victor.

“I was thinking that later on even though I wasn’t a cholo, the fact is in reality, whatever that means to you, I was a cholo. Because if somebody were driving by our car as we’re passing the joint around, they’re going to look in the car and say ‘Oh, it’s a car full of cholos,’ they’re not going to say ‘Oh, there’s two cholos in the front, and two chicano guys who really aren’t supposed to be there and are a little nervous about it,’” Daniel said.

To many, the cholo represents the violent and misogynistic culture that surrounds gang culture, Daniel said.

To dress like a cholo often means that others will assume you are in a gang, whether it’s true or not. This is also reflected in early Chicano literature that was masculine and violent toward women. Turning away from cholos in literature represents moving away from that toxic masculinity, Daniel said, and now the most prominent authors are women.

“What I’m saying with my book is there’s more nuances today to what it is to be a cholo. Because to be a cholo can be a matter of self-identification, a matter of identifying with a particular style, while at the same time not necessarily embracing those historically negative aspects of the subculture,” Daniel said.

While Kenneth claims to not speak for the cholo, he joined the Fresno Bulldogs street gang at 16-years-old and embraced those negative aspects of cholo life.

“The style of dress, the talk, the refusal to accept an inferior role despite poverty, and often a rocky home life, the pride of being who you are. That’s what led me from being a cholo to a gangster, and there is a difference,” Kenneth said. “I mistook being a Bulldog for showing pride in who I was.”

Kenneth says that in his experience, the three main aspects of cholo life are fortuna, familia and muerte (fortune, family and death). His crew was his family—the whole gang even got matching tattoos on the chest, over their hearts, of a bulldog.

He eventually found poetry, left the scene and got his master of fine arts degree in poetry from California State University. His past may seem like a lifetime ago, but there are times when it resurfaces. When introducing the gang he was a part of he said, “we” and “us” several times before catching himself and remarking that it was his old life showing up.

Kenneth’s collection of poetry, “The Cholo Who Said Nothing,” is about his previous life and his new one.

“I’m here telling these stories of homeboys that I grew up with, the ones that are still alive, the ones that are not in prison.” Kenneth said. “I’ve told them, ‘Hey I’m going to talk about you guys’ and I can’t imagine that they ever thought their lives would have been presented at the university. I mean, to them it seems like they don’t matter–no cholos allowed.”

He writes in his poem “My tattoos still speak,” “Should I lead the quiet life of a graduate/letting people point to me as proof that you can get out/whipping out my degree whenever I hear my tattoos speaking too loudly/should I dance around the English department of central California community colleges/become a full-time adjunct instructor dressed in tweed and targets reciting my favorite lines from twelfth night/wouldn’t that be like erasing my life’s true poem?”

Jeannie Pimentel • Sep 28, 2017 at 11:19 PM

What an immense testimony of the two cholos (Chacons) from Fresno, Ca who took the 180 degree turn in their life which is bringing chills maybe tears into the lives, and homes of those that long for hope whether for themselves or for their children. It is such a good feeling to see and hear that such powerful words are being used out there to encourage our youth these days. As a recovering drug addict of 26 years, I wish when I hear these two brothers speak out…I could have encouraged many myself. Your sacrifice… His (God’s) glory!

John 3:16.