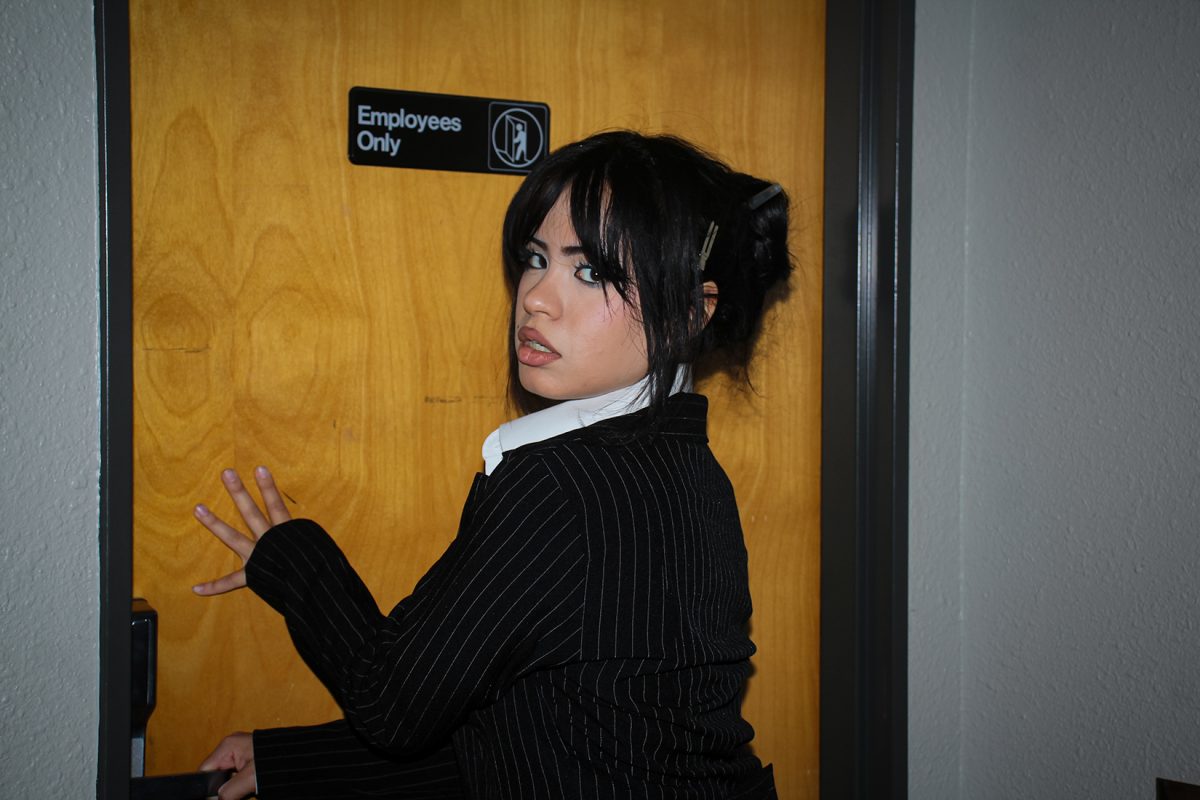

From the crowded metroplex in the Chicago area, to the West Texas town of El Paso, slam poet and Army private first class (PFC) Cecilia Tate, who goes by Tate, wants her poetry to “walk to whomever it needs to walk to.”

“You want to be able to change lives positively, send a positive message, to be able to get someone through the next day and the day after and the day after,” Tate said about her craft.

Her journey through the world of performing arts has not always been an easy one. While Tate recalls her sophomore year of high school as the pivotal moment in her poetry career, her struggles came at an earlier age.

“I started writing since I was in seventh grade in grammar school,” Tate said. “I haven’t always loved poetry, there was one point when I was very young and it was simple stuff like rhyming words like ‘your assignment is going to be rhyme green with whatever words you can think of’ and I found that to be very difficult.”

During her years at Marshall Middle School, Tate cited civil rights activist and poet Maya Angelou as the first one to inspire her to be more outspoken through her poem, “And Still I Rise.”

“I loved every minute of it,” Tate said. “It’s not just you telling your story, it is you being confident enough to speak on stage and it almost feels like a monologue.”

Things changed when Tate started high school at Curie Metro. The school allows for students to choose a major to direct their academic focus toward and she chose theater.

This posed new difficulties for Tate, as she had to switch tracks between two different writing processes.

“The moment when it became challenging was breaking my poetry voice and going into my acting voice because I was so used to performing speeches and poems,” she said.

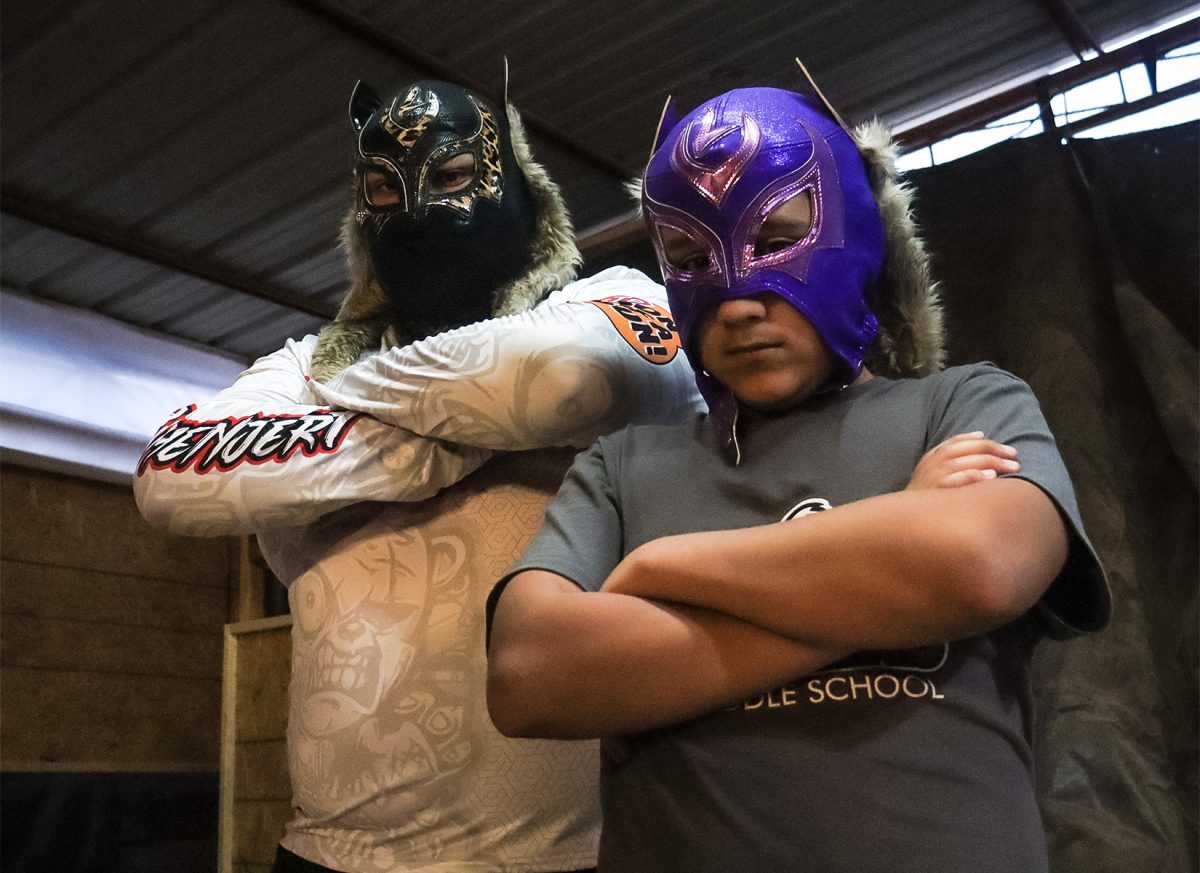

However, Tate has very fond memories of her high school poetry slam team Lyrical Revolution.

“There isn’t a day that goes by where I don’t think about Lyrical Revolution,” Tate said. “I miss it and the environment. I was a baby when I started; I didn’t know anything, so each stage was just learning, almost coping and growing, and that is what I got out of it.”

The teachings Lyrical Revolution left would carry on to future endeavors such as teaching and her military career.

“I learned how to be a teacher and how to be a team player,” she said. “I learned how to be a writer, how to identify myself as a writer and as a poet and a slam poet.”

During high school, Tate also learned the difference between being a slam poet and a poet.

“Being a poet is almost Shakespearian, you have to sit in a class for almost two weeks and you analyze this one poem,” she said. “Now being a slam poet, that poem that you perform should be visual, you should be able to read it and perform it almost as if you were watching it in a movie.”

Aside from Lyrical Revolution, Chicago also served as a source of wisdom for Tate, showing her the values of respectful competitiveness.

“Growing up in Chicago was an amazing experience since it is a performing arts city. It is very competitive, anything from dance to writing you name it it’s going to be competitive,” Tate said. “I see the drive when people hit the stage and they want to be better than the one before, but they also want to give the people that much more love and respect because they’re doing the same thing you are and it is not easy to stand up in front of 3,000 people and perform.”

Chicago also taught her the value of friendship and family-both lessons she carried over to her military career. However, Tate dedicates an even split of her time to her career and her poetry slam venture, and uses each experience to complement both aspects of her life.

After a drawn-out journey, Tate continues to seek open microphones around El Paso on the weekends.

“Poetry means breathing; it means walking in other poets’ footsteps,” she said. “Poetry is everything. It is my motivation it is what got me out of my comfort zone and made me able to talk to others and teach poetry is what developed me into the person that I am today.