Donald Trump campaigned on putting up a “big beautiful wall” between the border of Mexico and the United States. On Jan. 25, President Trump started the process to begin construction with an executive order called “Border Security and Immigration Enforcement Improvement.”

The act calls for the “immediate construction of a physical wall on the southern border” and is an expansion of the Secure Fence Act signed by former President Bush in 2006. The act also increases the number and operational capacities of detention facilities to “detain individuals apprehended on suspicion of violating federal or state law, including federal immigration law” and gets rid of the “catch and release” practice, where until an individual goes to immigration court they are not held in detainment facilities.

Sanctuary Cities

Trump also signed another executive order the same day called “Enhancing Public Safety in the Interior of the United States,” which threatens so-called “sanctuary cities” by withholding federal funding if they do not comply with Immigration Customs Enforcement’s request of identifying and detaining all individuals who are undocumented.

However, the vagueness of the term “sanctuary city” makes it difficult to tell which cities and towns will be affected by this order, and cities who are called sanctuary cities state that the local police force is not a federal agency and do not want to enforce federal law.

El Paso is considered a sanctuary city by some anti-immigration advocates because the El Paso Police Department does not specifically focus on finding undocumented individuals. However, El Paso does not consider itself to be one because it generally does honor requests to hold and detain certain undocumented immigrants.

In Texas, Governor Greg Abbott has said that he will oust any elected official who “promotes” so-called sanctuary city policies. He has also said he will cut funding for those cities.

“Many of those grants, a lot of people don’t know this, especially in El Paso, $3.8 million that Gov. Abbott is threatening to take affect children who are victims of child sex trafficking, women against violence, training programs for sheriff deputies and juvenile justice programs for kids,” said Texas state Rep. Cesar Blanco at a recent legislative forum.

Cost of the wall

What the wall will look like or how much it will cost is not yet clear. President Trump’s executive order is a step toward construction, but does not outline what form the wall will take. It defines the wall as “a contiguous, physical wall or other similarly secure, contiguous, and impassable physical barrier,” but that can take as many forms as already exist in the more than 600 miles of walls, fences and posts that line the southern border.

“What the government hasn’t told us is how much it’s actually going to cost, so the estimates are between 10 and 40 billion dollars,” said Josiah Heyman, director of UTEP’s Center of Inter-American and Border Studies.

While the cost may not be clear, the effectiveness of a large barrier to “maintain complete operational control of the southern border” is well documented.

“It’s generally recognized by enforcement people inside the government, who have been quoted inside the newspapers many times, and those of us who are external experts on homeland security, that the fence slows people down, but it doesn’t prevent them from crossing,” Heyman said. “It’s a big expensive multibillion-dollar political symbol, not really an enforcement measure.”

John Kelly, the newly appointed secretary of the Department of Homeland Security, said “a physical barrier in and of itself will not do the job. It has to be a really layered defense.”

In Texas, all 36 State congressional members and two Senators are against the wall. Large portions of the proposed wall go over private property and the federal government would have to use eminent domain if the owners did not wish to sell.

Rep. Will Hurd, R-Tx, said in a statement that the “Big Bend National Park and many areas in my district are perfect examples of where a wall is unnecessary and would negatively impact the environment, private property rights and economy.”

Asylum seekers

In fact, the wall will not prevent the majority of those wishing to immigrate to the United States for the simple reason that they are not running away from law enforcement, but toward it. Asylum seekers from Central America, specifically Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador, make up for more than half of those who are arrested at or around the border.

According to the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse, a data-gathering organization at Syracuse University that collects, among other information, enforcement activities of immigration officials, immigrants from those three countries in Central America made up 121,471 immigration-related arrests out of 199,223 total arrests in 2016, while Mexican immigrants trail at 39,528 arrests.

Although some immigrants are asylum seekers, they are still counted as an arrest, which distorts the data available. Advocates for stricter immigration policies, who reference the number of arrests, are actually including the number of asylum seekers as well.

“This has been known for a number of years now (that) the majority of people arriving at the border are not Mexicans—they’re Central Americans,” Heyman said. “They’re arriving for asylum. They’re not arriving simply as unauthorized workers, and they’re literally not blocked by this enforcement mechanism. It’s not like they’re not prevented from coming into the wall, because what they do is walk up to law enforcement officers and surrender.”

The total number of undocumented immigrants from Mexico has been in steady decline since 2007, according to the Pew Research Center. While the number of asylum seekers from Central America seeking refuge from gang violence, sexual assault and poverty have steadily been on the rise since the 1990s.

President Trump’s wall will instead force those who are not seeking asylum to take more drastic measures across more desolate regions and by paying more money to coyotes, who smuggle people across the border.

Environment

The wall will also have a significant affect on animals and flora, according to UTEP political science professor Irasema Coronado, who was appointed by former President Obama to be on the Joint Public Advisory Committee of the Commission for Environmental Cooperation.

“When you build anything—a wall, a barrier—or you put cement planks or steel planks up on the wall, you’re going to fragment that habitat for animals and flora and fauna,” Coronado said.

Overshadowed by the wall

While the wall may not have the most effective influence when it comes to immigration, it gets the most attention. The second executive order President Trump signed that day will actually have a broader and larger impact.

As of now, there are immigration cases that have a backlog of over 600 days. That is because the immigration court does not have enough resources to get through a number of asylum seekers and other immigration cases.

“This means (those) who legitimately have claimed to asylum are taking forever, many of them in detention or at least part of the time in detention before they can get it resolved,” Heyman said.

The executive orders passed by Donald Trump fail to address this concern, and instead exacerbates the issue by pressuring counties and cities with a high immigration population to process all individuals whose status is in question, or risk losing federal funding.

The increase in blanket deportation also makes it difficult to find the estimated 13 percent of undocumented immigrants with criminal convictions, according to the Migration Policy Institute.

Trump’s executive order attempts to curb this difficulty by increasing the total amount of border patrol officers and immigration and customs enforcement agents by 15,000.

This increase will be one of the largest since the early 2000s, when former President Bush made the Customs and Border Protection agency the largest federal enforcement agency in the country.

The move by Bush also had the unintended consequence of increasing the number of abuses by immigration agents and by custom’s and border protection officers at the ports of entry. According to an investigative report by Politico, between 2005 and 2012 there was an arrest each day for misconduct by border patrol agents.

James Tomsheck, former chief of internal affairs with Customs and Border protection, told the Center for Investigative Reporting that corruption “was an undetected problem and far more severe than the actual number of arrests.”

“Another concern I have is that people are emboldened to say and do things that they feel the president wants, and I feel that might have overzealous border patrol agents, overzealous immigration agents that will take this (executive order) as a mandate to go above and beyond their duties and responsibilities,” said Coronado.

Despite the future increase of border security, people will still try to come to the United States, whether it be for work, to see family or to escape persecution. By making it more difficult to come to the US, they must rely on groups that have more resources and know-how to get across the more dangerous and desolate parts of the border, namely coyotes.

“Now you have this much more vulnerable and exploitable people who don’t have the same connections,” Heyman said. “You have (an) increasing entry of scarier and more sophisticated and more coercive criminal organizations into the business of human smuggling. What building a bigger, longer wall does is simply reward the people who can bypass it more.”

Left behind

Left to the whims of the changing executive administration are those who have been separated from their families for years, even decades.

The Correa family has been separated by the US/Mexico border for more than 10 years.

Getting the right paperwork is often a matter of time, often decades, as well as a matter of money. Hugo Correa has not been able to change his status since crossing the border and has since remained separated from his family.

“We got together and he came over here, and I’ve been trying to get paperwork for him, but it’s very difficult,” said Claudia Correa, Hugo’s wife who accompanied him.

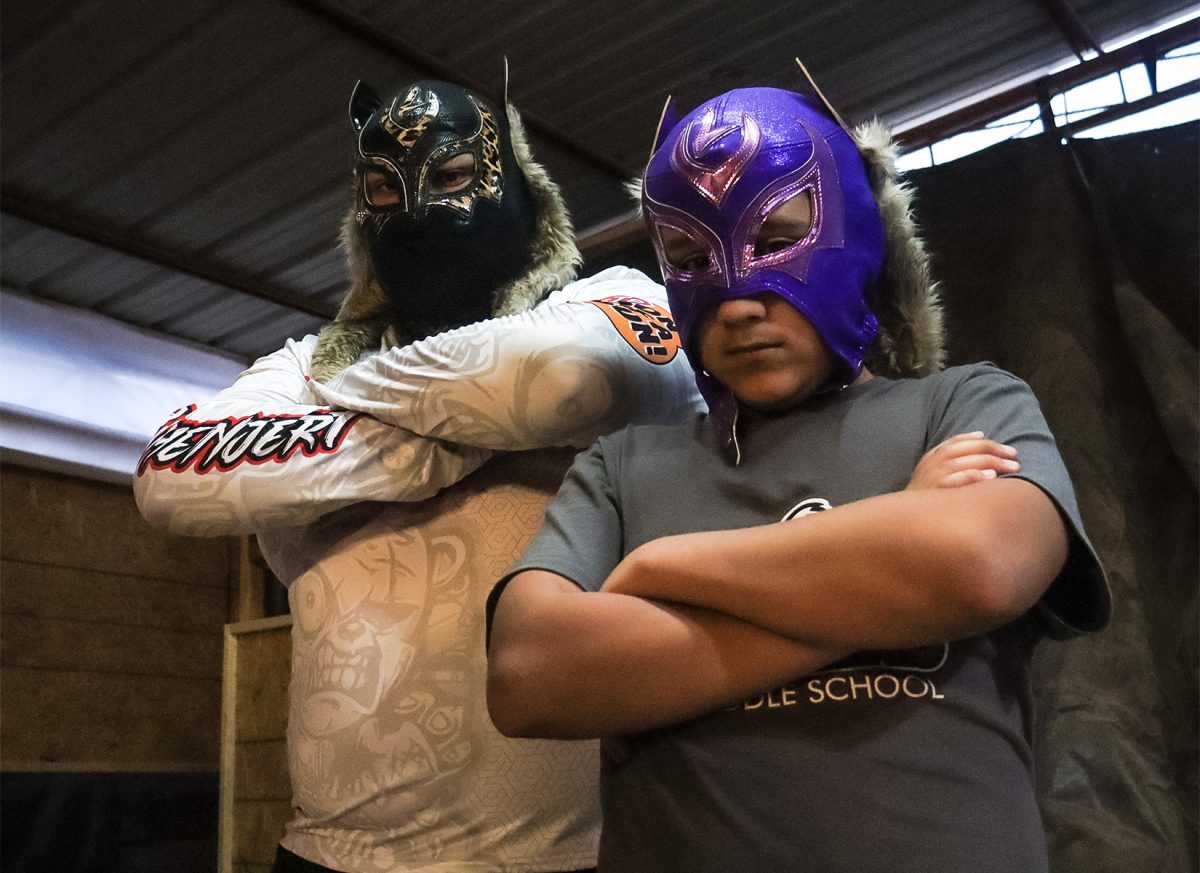

The Correa family was briefly reunited due to the #HugsNotWalls event on Saturday, Jan. 28, where families who live on opposite sides of the wall could meet for three minutes without fear of deportation.

Mariela Ramos had only seen her Dad once when she was 7 years old, she is now 25.

“I’m really excited, I’m so pleased that they did this event. I mean he’s really sick and I thought I was never going to see him again,” Ramos said.

It was third time #HugsNotWalls was able to cross barriers and bring families together, but thousands are not as lucky as the Correa family or Mariela Ramos.