He staggers around the Rescue Mission with the book “What Jesus Demands from the World” with a melancholic expression on his face. Bronko Belichesky, a former UTEP Miner kicker from 1974-76, is living at the cost-free facility after he was diagnosed recently with congestive heart failure.

Now, the 72-year-old ex-football field goal kicker wants to make use of his days by offering his help to younger athletes, free of charge, at the sport he once loved.

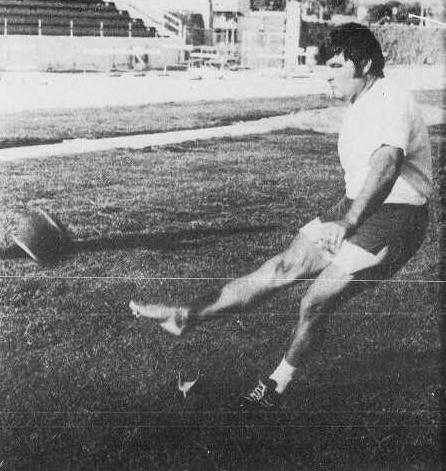

He was a barefoot kicker, infamous for his braggadocios play. He held the UTEP record for the longest field goal in history for nine good years, all part of an illustrious collegiate career with wide local fan support; followed by a storied career beyond football.

“I was the best in this game,” Bronko, as he prefers to be called, said. “I could kick a ball a fucking mile.”

His love for the game began when he was nearly 12 years old and his cousin took him out to play football. He is from Macedonia, the son of a minister who brought the first Eastern Orthodox Christian church to El Paso, and he hardly spoke any English. But as soon as he stepped onto the gridiron, he was a natural-born talent.

“My first memory was on defense. My cousin told me, ‘if the quarterback comes your way, your job is to stop him any way possible,’” Bronko said. “So he came by and I ripped his fucking head off. They put in another quarterback and I knocked the fucker cold too. Dynamite in action.”

Throughout his adolescent days, Bronko continued the sport of football and focused more on his kicking game. After high school, he joined the Marine Corps, where he continued to play ball. Although the team was not winning games, Bronko got to see some of the nation’s best teams like Ohio State, Michigan and other teams from the Big East.

But, after he had served his time with the Marines, Bronko had no clue where to go. His cousin, the same cousin who introduced him to football, suggested that he spend some time at a junior college.

“I had no clue what a junior college was,” Bronko said. “My cousin said, ‘it’s a two-year program and if you make it there, you can go to a four-year program, and if you make it there, you will make it for life.’”

His impressive field goal shot wasn’t just amazing because of its raw power; oddly enough, he did it all barefoot, claiming that it helped with accuracy.

“I’d hit 99 out of 100,” he said. “I had trajectory no one could understand. All my coaches would wonder ‘how the hell could he do that?’”

He spent most of his time practicing in the Los Angeles City College basketball gym, where he would stand on one end of the court and nailed the ball through the basket holsters on the opposite end.

Football was his life, so Bronko had to follow his dream to keep it alive. He played at LACC from 1972-73. Most of the players from the college went on to play for USC, but there was one specific reason Southern California wasn’t on the kicker’s mind.

“The USC coach John McKay went to a lot of our practices and games, but I didn’t like his arrogance,” Bronko said about the legendary coach, who had won four national championships for the Trojans in just a little over a decade. “I didn’t like his attitude. He said, ‘you think you’re good kid?’ I said I’m the fucking best, you don’t know no one better.”

For his efforts in Los Angeles, Bronko was invited to try out and visit all the major teams across the nation. He impressed teams like Michigan State, Ohio State and Michigan greatly.

“I went to visit all the schools—I didn’t care if they were an all-white school or an all-black school,” Bronko said. “I didn’t have a racist bone in my body. In fact, I believed that America created the racist environment. Where I was from, skin color had nothing to do with anything.”

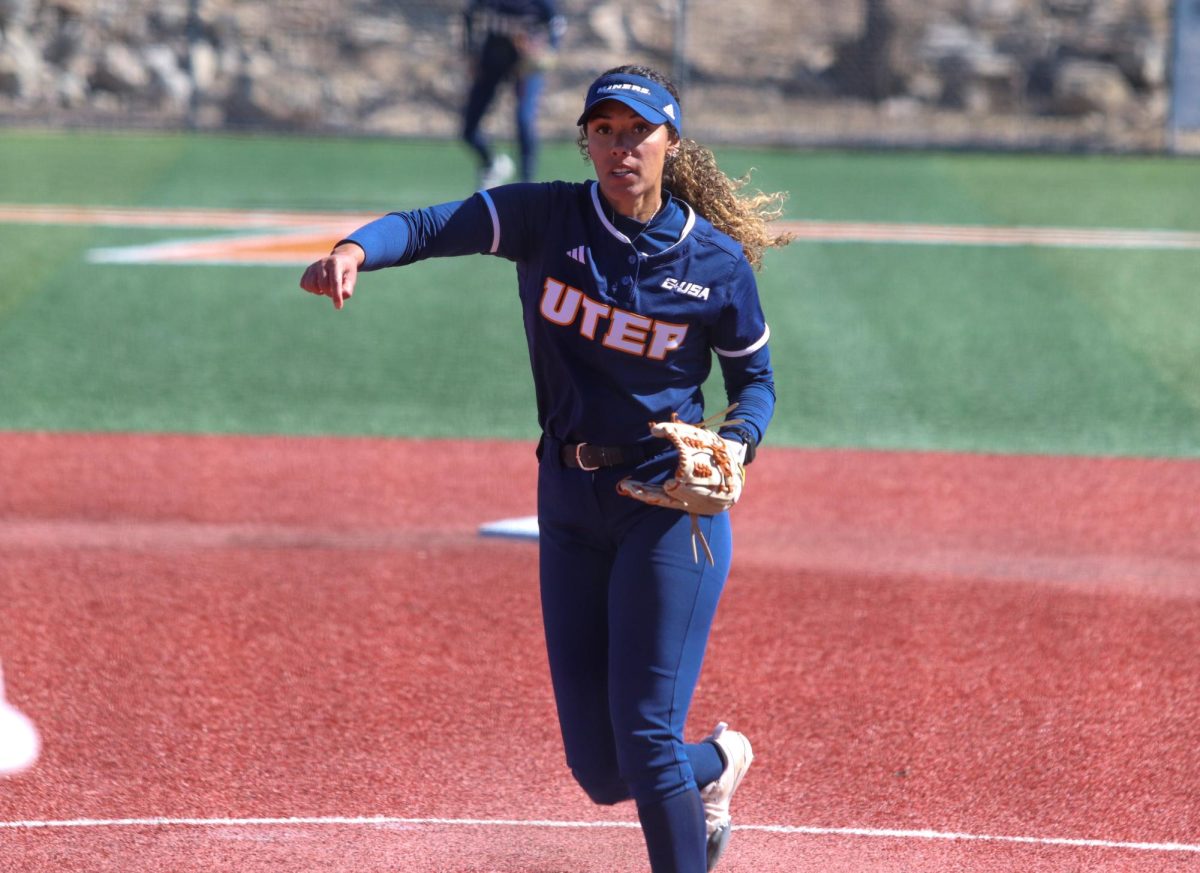

He chose UTEP because he loved the weather, the people and the coaches. During his first season in 1973 under head coach Tommy Hudspeth, the Miners were dismantled on the year and posted an embarrassing 0-11 record. Some of the harsh losses included an 82-6 loss to Utah, 49-0 loss to New Mexico and a 63-0 loss to BYU. Despite his team’s rough season, Bronko knocked in 20 field goals and was their strongest resource on special teams.

After Hudspeth’s miserable one-season journey, he was fired. In 1974 Bronko and the Miners were under the direction of Gil Bartosh. Under the new coach, the Miners began to make strides and finished 4-7 in the WAC.

One of the best wins that season for the Miners, and for Bronko, was against Arizona State. They played the same Arizona State squad, who under head coach Frank Kush had won five WAC conference championships in a row. Bronko had 24 points, 8-for-8 on field goals throughout the game, including a 57-yard booming field goal. The Miners pulled through in a tight game, 31-27.

“I walked up to Frankie (Kush) before the game and I said, ‘Frankie, I’m dedicating this game to you. I’m going to make you have nightmares of me when you sleep at night,’” Bronko said. “After the game, I reminded Frankie that I was the greatest he had ever seen. He (Kush) told me, ‘Bronko, you talk too much. You need to keep your mouth shut.’”

After his illustrious collegiate career with the Miners and LACC, Bronko decided to enter the NFL draft. The Dallas Cowboys picked him up with the intention to play him immediately. Instead of taking a longer, guaranteed contract, Bronko wanted a signing bonus for being drafted.

“When I was in Dallas, I roomed with Randy White, and a couple weeks into the preseason I told him, ‘Randy, I don’t want to do football anymore; I’m going to go to Harvard law school,” Belichesky said. “Randy couldn’t believe it, but I told him that if I ever got hurt, I would be without a job and have nothing to fall back on.”

Bronko used his signing bonus and the superb grades he had in college to go to Harvard to get his law degree. Following Harvard, Bronko practiced law for 27 years in California and then moved back to El Paso.

“I have no regrets for what I chose to do,” he said with a stern look. “The game is the game and the game isn’t my whole life.”

Reflecting on his experiences, long practice hours and different squads, Bronko believes that truly anyone can do what he did with determination. His advice to the younger kickers getting into the sport is simply to practice.

“Practice—while others are asleep, you keep practicing,” he said. “There’s not many kickers in the game who have ambition. There’s not many good kickers right now.”

Now, because of his disease, he is confined to his home at the Rescue Mission and lives day-by-day with his terminal illness.

He does not like to talk about it; in fact, the talk of his heart failure pains him. He doesn’t like to talk about how he got to the center that attempts to help those who are less fortunate.

He prefers to not explain how he got there, or how he left his nearly three decades of legal practice. El Paso County court records show that he was cited for practicing law without a license in 2012. He never talked about that either.

What is for certain is he shivers at the thought of another heart attack, possibly in denial of what could come in his future.

However, Bronko wants to give back to the youth playing the sport before his time on this earth is gone, and is willing to offer kicking lessons and other football training free of charge to anyone willing to learn the ropes of the game.

Bronko asks that he be reached by phone at 915-474-4744. If not for training for a future football star, perhaps as a way of just reaching out to one from the past.

John Hahn • May 4, 2017 at 2:58 PM

Bronko was awesone, nice person and I was firtunate enough to play on same team and snap the ball to our holder on a lot of his field goals.