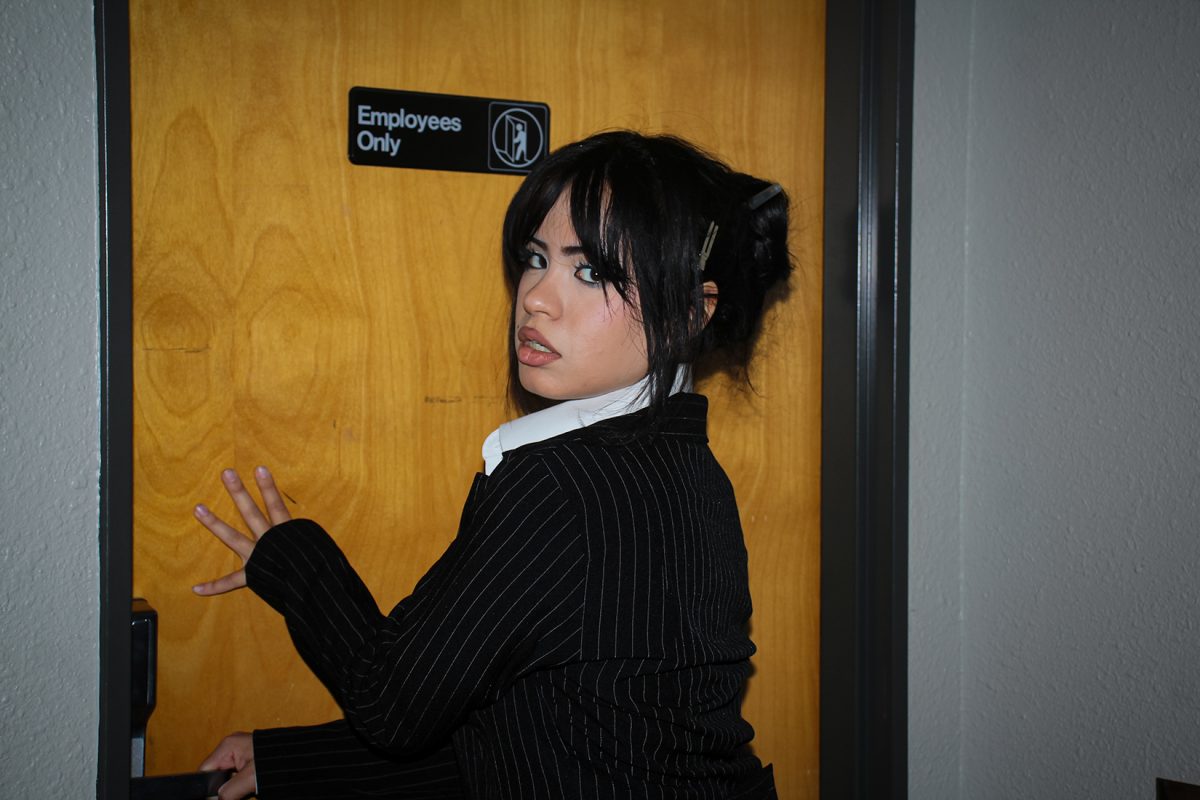

If a person’s appearance is tied to their culture, but is not permanent, that person can now legally be denied employment. UTEP’s Black Student Union set up a protest photo shoot on Sunday, Sept. 25 at Leech Grove to stand in support with those who have faced natural discrimination nationally and internationally throughout the last few months.

At the start of this school year, students at Pretoria High School For Girls, a public school in the capital of South Africa, reported that staff would tell them that “they look like monkeys, or have nests on their heads.” The girls began spreading the hashtag #StopRacismAtPretoriaGirlsHigh via social media and it wasn’t long before they received international attention.

“We experience the same things here in the states,” said Shyla Cooks, senior biology major and president of the BSU. “Often natural hair is looked down on as being ugly or needing to be tamed in all settings.”

According to the Pretoria school’s code of conduct, student’s hair must be brushed and neatly tied back. Although cornrows and braids are allowed, they must be at a maximum diameter of 10mm and girls are not allowed to have Afros.

Cooks noticed the PHS girl’s bravery to protest and said that even though they’re in a place as remote as El Paso, they felt they should still give the girls a voice.

“It’s so ridiculous that it’s hair because it’s self identity,” Cooks said. “Your natural hair identifies you, why should you be stopped to wear your hair?”

Just a month after the South African students protested their right to natural hair, the U.S. 11th Circuit Court of Appeals upheld employers’ right to deny potential employees based on their hairstyle. In 2010 in Mobile, Alabama, Chastity Jones, a woman with dreadlocks, was getting ready to start a job when human resources let her know she could not keep her dreads because according to company policy they “tend to get messy.”

The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission took Jones’ issue to court and on Sept. 15, in a 3-0 ruling, the court agreed that dreadlocks are not immutable (unable to be changed over time) and employers are allowed to ask employees to change that.

“One time in high school, I came to school with my (natural) hair and people were like ‘why is your hair like that?’ ‘Why don’t you pick it out?’ or ‘Why don’t you cut it off?’ ‘Why is your hair so nappy?’, said junior Antton Robinson, vice president of the BSU. “You don’t want to just conform to everyone else’s standards because you conforming basically means you’re giving up being yourself—you’re giving up being black.”

The natural hair movement is something sophomore nursing major Sonia Mugeni has been practicing since she was a junior in high school, even after she was told it looked unprofessional and she would get feedback such as, “Oh, why are you wearing your hair like that? It looks ugly, it looks dirty.”

Mugeni said her family also frowned upon her hair choice.

“I’m the first one in my family to go natural,” Mugeni said. “My family would say, ‘What are you doing? Why can’t you just relax your hair? It looks horrible. It looks like you haven’t combed it.’”

At the protest, Mugeni held a sign that read, “I could care less if I make you uncomfortable.”

“I love my natural hair, I don’t think I’ll ever go back,” she said.