At the tail end of 2015, in mid-December, the Mexican census bureau made history by recognizing their black citizens in their latest national census survey. The inclusion represents the first official recognition of African heritage within Mexico.

In November 2015, a Black-Mexican activist group called Mexico Negro launched a campaign to have Afro-Mexicans listed in the national census. Since the turn of the 20th century, Afro-Mexican identity has been pushed aside.

The all-encompassing term—Mestizaje—was used to cloak any Mexican of interracial ancestry, while African lineage was swept under the rug. Prior to the national survey that went out on Dec. 8, Mexico was one of the last Latin American countries to recognize its black population.

Nearly 1.4 million Mexicans identified themselves as Afro-Mexicans or Afro-descendants in Mexico’s 2015 national survey. The total comes out to 1.2 percent of the population, but Afro-descendants make up a bigger piece of the pie in the Americas.

According to the Department of International Law (DIL), there are approximately 200 million people of African descent in the Americas, with Brazil having the largest black populous of any Latin American country. Mexico finally acknowledging African descendants is a step in the right direction to start retelling Afro-Mexican history.

“Other Mexicans tend to see visible Afro-descendants as foreign because Afro-Mexico history has been erased from the textbooks and our memory,” said interim director of the African American Studies Program, Selfa A. Chew Melendez. “We don’t know that ‘we are them’— that Mexico is African also.”

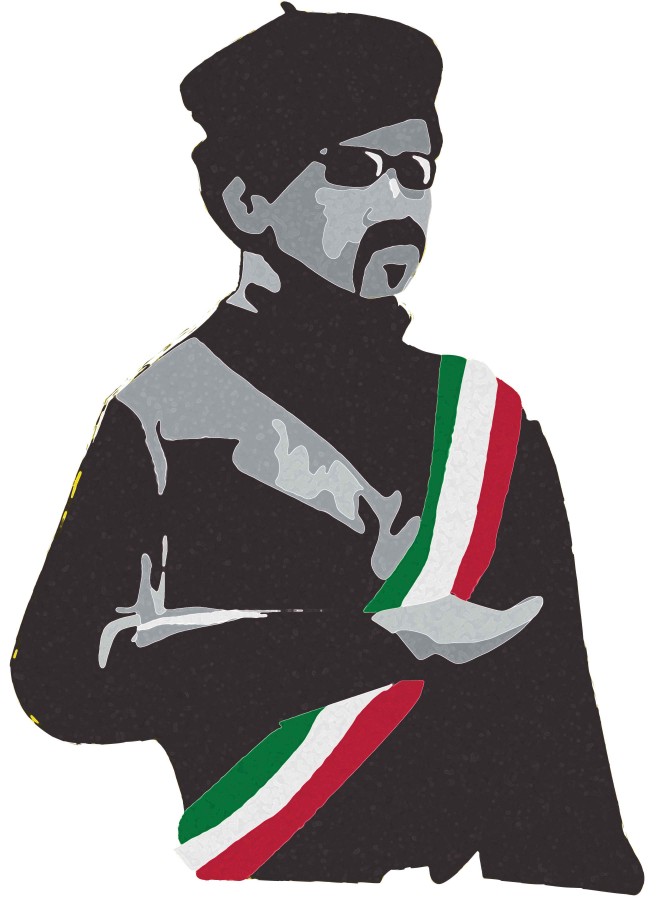

Going back as far as the 16th and 17th century, there were men and women of African descent. Arguably, history’s most forgotten Afro-descendant figure is Vincente Guerrero, the second president of Mexico, who was called “El Negro.”

Most would consider 2008 a landmark date in North American history, as Barack Obama became the first black president of the United States, but 179 years earlier, Guerrero was the first black president of a North American country.

More notably, Guerrero fought to abolish slavery, while Mexico gained its independence from Spain in the Mexican War of Independence.

“He (Guerrero) made sure the constitution he helped write included the right to freedom,” Chew-Melendez said. “Erasing racial categories was considered a path towards democracy; however, the colonial hierarchy had already institutionalized racism and Afro-Mexicans (today) have very limited resources.”

According to Chew-Melendez, three of the largest Afro-Mexican populated states, Guerrero, Oaxaca and Veracruz, rank amongst the poorest states in the country, due to limited access to education, productive land, employment opportunities and medical care.

The 2012 statistical annex of poverty in Mexico showed that Guerrero, Oaxaca and Veracruz ranked as the second, fourth and ninth poorest states in the country, respectively. Chew-Melendez attributed the correlation of Afro-Mexican populated cities and poverty to structural racism.

“It is the same case with indigenous communities,” Chew-Melendez said. “Across this border the Raramuri community is a displaced indigenous group with huge problems. The 43 teacher students from Ayotzinapa, most of them are from Afro-Mexican communities, were denouncing the extreme inequality in the state of Guerrero because of their own experiences with structural racism.”

As defined by the Aspen Institute for Humanistic Studies, structural racism is a system in which public policies, institutional practices, cultural representations and other norms work in various, often reinforcing ways, to perpetuate racial group inequity.

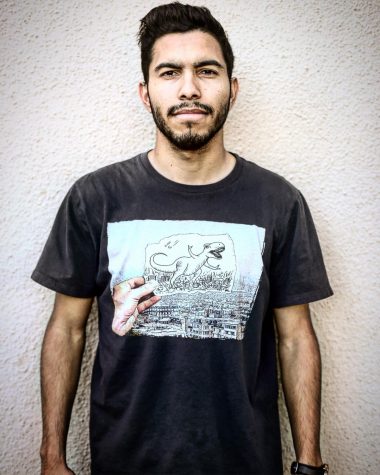

Even Omar Escobedo, a native of Chihuahua City has seen how Afro-Mexicans could be treated differently because of the color of their skin.

“I think they struggle more,” said the sophomore industrial engineering major. “It has to do with the color of their skin, they are discriminated against. It’s not that much, but I have seen cases. They can get a hard time, and professionally it can be hard.”

Now that Mexico has taken a step in recognizing neglected minority groups, the next and even broader step, according to Chew-Melendez, is providing the essential needs to all Mexicans, no matter their identity.

“Mexico has taken a step towards recognition of the third root,” Chew-Melendez said. “Now the Mexican government has to work to make sure that every resident of Mexico gets access to higher education, proper medical care, dignified employment and a safe environment to thrive, regardless of racial, ethnic, gender or sexual identities.”

Javier Cortez may be reached at theprospectordaily.news@gmail.com.