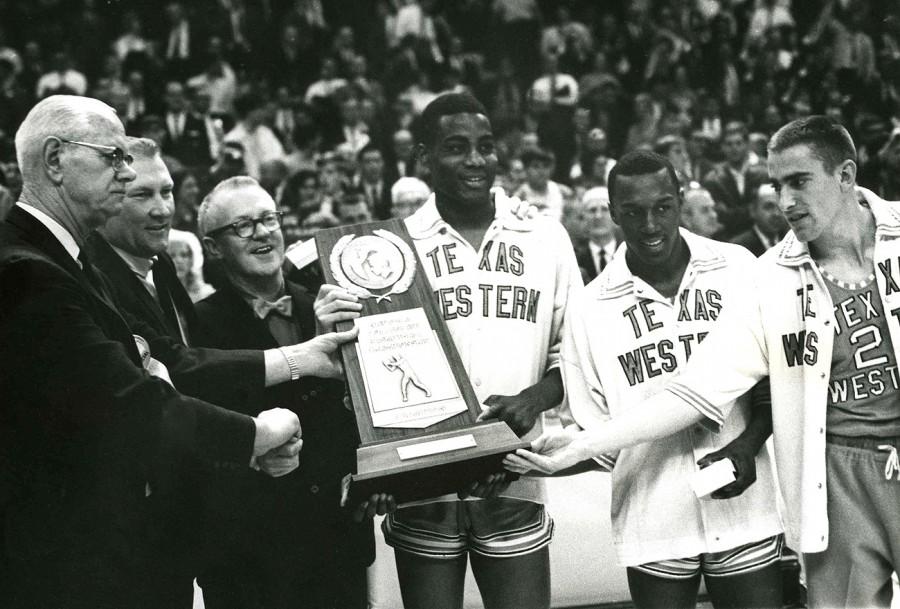

Even if it wasn’t clear to everybody at the time, there would be a before and after to March 19, 1966. At a time when the NCAA Tournament was nowhere near the national spectacle it is today, Texas Western’s (now UTEP) victory over Kentucky to claim college basketball’s biggest prize was not at the forefront of national issues. It was in El Paso though. El Paso knew how important it was. The city that was home to the new National Champions knew of the game’s importance, and it would have as much as of a lasting effect on its community as it did on the nation as a whole.

“It changed everything for us, it’s been a wonderful thing for El Paso,” said Ray Sanchez, the assistant sports editor at the El Paso Herald Post during the 1966 basketball season. “One of the greatest things that has ever happened to El Paso.”

Next March will mark the 50th anniversary of Texas Western’s historic victory and UTEP Athletics along with the city as a whole will use the whole 2015-2016 basketball season to celebrate the success the Miners experienced during that 1966 season, in which they won 27 games, lost just one, and would change the city, starting with sports itself.

Today, basketball is one of the marquee programs at UTEP. It holds as much importance and relevance as football, but that has not always been the case. According to Sanchez, before Don Haskins came to El Paso to take over the Miners’ bench, basketball was no more than an afterthought at the college and in El Paso.

It was so irrelevant that prior to the 1960s, the coaching duties were even assigned to football trainers or assistant trainers. The coverage was minimal and the interest of the El Paso community in the team was almost inexistent.

“I wouldn’t dare guess how many, but it was very few,” Sanchez said when talking about the amount of people who would attend Miner basketball games before the Haskins era. “Hardly ever got any write ups, like football used to. It was considered more like track or more like a minor sport.”

The indifference disappeared as the team began to experience success, to the point where all of El Paso was aware and fully invested in the Miners and their quest for glory. The celebration and joy around the city thanks to Haskins and his squad was unprecedented and has yet to be replicated.

“People were out in the street, honking horns,” Sanchez said. “Students at the school started burning bonfires, the police and the fire department had to go out and try and extinguish them. The whole city went into a sort of wild crazy thing.”

Sanchez vividly recalls the fire department’s struggles when dealing with the bonfires created by the students in celebration. As the firemen attempted to extinguish the bonfires, the students would park their cars on the hoses impeding the flow of water.

Thousands showed up at the airport to greet the national champions, and in Sanchez’ opinion the championship would catapult El Paso to grow to what it has become today.

“It seems that ever since they won that championship, El Paso just burst,” Sanchez said. “It put us on the map. I’m sure it has attracted students to the school, it has attracted people to El Paso to come here and live.”

As it has been well documented, the impact of the game went far beyond the court and reached people well outside the El Paso city limits. Gary Williams was a student and basketball player at the University of Maryland, where the national championship game was hosted. He was present at the game and recalls the social impact it had on those in attendance.

“There were so many stereotypical notions about black ballplayers then, particularly the farther south you got. Mostly, it was presumed they were undisciplined and stupid,” Williams said in a 2006 interview with Mike Wilbon. “But that night, watching the way Texas Western played, if you had stereotypes in your head about basketball and you were in Cole (Field House), it changed the way you thought, changed the way you felt. It’s very seldom that one event, that something which took less than two hours, could affect people so dramatically.”

The championship game, which was the first time five black players were started against five white players, debunked many of the myths concerning African-American athletes and aided the fight for equality amongst races. In El Paso however, the racial tensions that swept most of the nation, were really non-existent.

El Paso and Texas Western College had a history of progressive thinking and ignorance toward division of races, especially compared with the rest of the south.

In 1956, Charles Brown became the first African-American athlete in the history of Texas Western and the first in any of the major southern institutions. It was not until 1966 that another southern school recruited an African-American athlete.

In fact, it is said that the city, the coach and the team itself was not really aware of the racial implications the game against Kentucky, until much later. Still, it is another source of pride for El Paso and a reason why the championship is so celebrated.

“El Paso has always been at the forefront of civil rights,” Sanchez said. “They (the Miners) lifted us, El Paso, by proving that you know, now we were looked at not only as champions, but as champions of civil rights too.”

Although the social impact or change was not as great in El Paso as it was all over the nation, and was recognized as the most important game in the history of basketball, the result of March 19, 1966 had an important and long-lasting effect on the Sun City and its people, unlike it had experienced prior or has experienced since.

“Nothing like this, this was the greatest thing sports-wise to ever happen to El Paso,” Sanchez said. “It changed everything. It put us on the map, made us proud, made us happy and we’re still celebrating even now.”

Luis Gonzalez may be reached at [email protected].