The number of sexual assaults reported on college campuses is rising. But officials and advocates agree that the increase means more students are coming forward, not a growing number of assaults.

Amid a national conversation about sexual assault prevention and response, the Department of Education Office of Civil Rights is investigating 105 colleges and universities for civil rights violations under Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972. Reports of sexual assault have risen 140 percent at these schools from 2008 to 2013.

Title IX prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex, which can include harassment and violence. The law applies to any private or public educational institution that receives federal funding. The complhttps://www.theprospectordaily.com/wp-admin/upload.php

aints against the 105 schools allege that the colleges and universities violated complainants’ Title IX rights by failing to respond adequately to reports of sexual assault.

High numbers of sexual assault reports may look discouraging, but more assaults being reported being reported is a positive step for a notoriously under-reported crime, Alison Kiss, executive director of the Clery Center for Security on Campus, said.

“I think one thing at the Clery Center we talk about is that higher numbers are not necessarily bad,” Kiss said. “It means that students are coming forward and reporting, and that’s really great.”

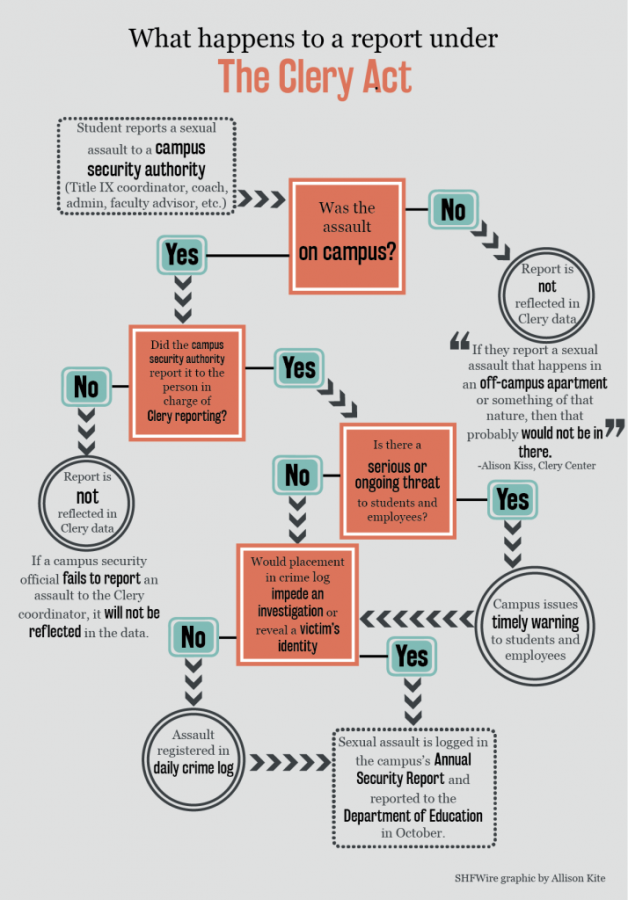

The Clery Act requires schools to report crimes that occur on or around campus. Campuses must report the preceding three years’ data each Oct. 1, broken down by type of crime.

For many of the schools under investigation, record-reporting years for sexual assault or “forcible sex offenses” coincide with the opening of their Title IX investigations. Fifty-six schools reported an increase in sexual assaults the next time they reported to the Department of Education, following the opening of their Title IX investigations. Increases showed up frequently in the 2013 data – filed in October 2014 – for schools put under investigation from October 2013 to September 2014.

At some schools, the reports have increased by one additional assault, but others – including Swarthmore College – reported more dramatic increases. The number of reports increased slightly after Swarthmore was put under investigation in July 2013, but reports increased by 642 percent the following year.

Many schools, however, had increased reports at least a year before they became subject to a Title IX investigation. It isn’t clear if there is a link between the investigations and reporting spikes, or if one is driving the other.

“It’s hard to say, but I suspect it’s a little of both,” said Saunie Schuster, a partner at the National Center for Higher Education Risk Management, a legal consulting firm that works with colleges and universities. “As more people within a campus are engaging with reporting, the scrutiny of the way in which a school’s responding is increasing as well.”

Reporting spikes are not limited to schools under investigation. Colleges and universities in general have reported increases in recent years. Average reports for schools under investigation, however, have risen faster — up 140 percent — while overall reports of sexual assaults rose 75 percent.

A major contributor to the increase is a large-and-growing national conversation. From a Dear Colleague letter OCR distributed in 2011, reminding schools of their Title IX responsibilities, to growing student advocacy movements, the increased attention may be driving reporting.

“Sometimes it’s just the publicity itself that draws attention to the issue,” Corey Rayburn Yung, a professor at the University of Kansas School of Law, said. “A decision to report for a sexual assault or rape victim is a difficult one, and sometimes the attention to it can make them realize how important it is for them to come forward and report that there’s a sexual assaulter on campus so that there aren’t more victims.”

Yung wrote a study in Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, a journal published by theAmerican Psychological Association, that demonstrated widespread under reporting of sexual assault at 31 large universities. Those schools were subject to Clery auditsfrom 2001 to 2012. During the audits, schools’ reports of sexual assault increased by an average 44 percent, while reporting rates for aggravated assault, robbery and burglary remained consistent. When the audits were over, sexual assault reports decreased to pre-audit levels, even at schools that were fined.

As long as the federal government didn’t peer over schools’ shoulders, they swept sexual assault under the rug, the report said.

Aryle Buter, a consultant at End Rape on Campus and a complainant in Clery and Title IX complaints against the University of California-Berkeley, said she was concerned that the spike for OCR-investigated schools reflects a similar practice of under reporting.

“I realized that the most OCR was going to do was look over the university’s shoulder for a couple of years, perhaps get them to change a few things in the short term,” Butler said. “But overall, they were simply going to revert back to the practices that they had had for years.”

Yung, however, drew distinctions between the two investigations. Title IX investigations have drawn a great deal of student, media and public attention, which drives reporting rates up to some degree. Title IX investigations concern only policy surrounding sexual assault.

Clery audits held a microscope to all campus crime, but, according to the study, sexual assault numbers were the only ones that changed.

The national conversation has drawn attention from campus administrators as well as students, which may mean better practices, Kiss said.

“I think when an institution is under investigation, in my experience, even before there’s a finding from either a Title IX investigation or a Clery investigation, is that an institution does start to kind of do a self-study and self-assessment and change what they’re doing,” Kiss said.

The student, government, campus and media attention have created an opportunity for conversation, which Schuster said began with the 2011 Dear Colleague letter.

“I call that spring term the term of terror for higher education as they began their realization of their obligations for accountability under Title IX,” Schuster said. “It spawned and created the wonderful opportunity for empowerment of individuals who genuinely didn’t feel that they had a voice prior to that – a voice that was respected and heard.”

Reach reporter Allison Kite at [email protected] or 202-408-1491.