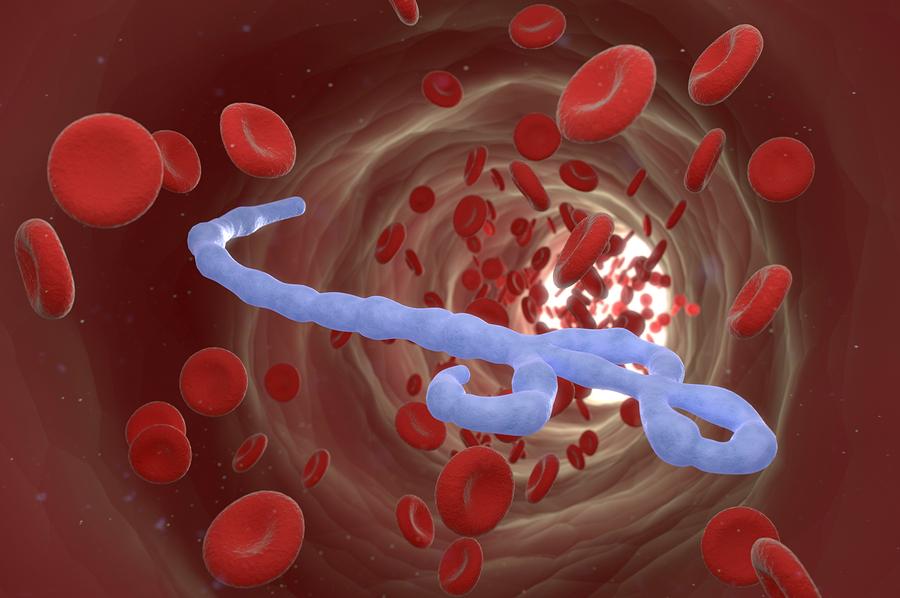

For Douglas Watts, an infectious disease researcher and executive director of the animal care center, the Ebola virus is nothing new.

Watts began working with Ebola back in the 1980s, when he worked for the U.S. Army’s medical research team, where he conducted research on highly infectious diseases of humans and animals overseas, including Ebola.

“I wore a space suit for eight years and my question that I was trying to answer with Ebola was: how is Ebola transmitted?” Watts said.

In the lab, Watts infected mosquitoes, ticks and sand flies with the virus. He also worked on developing diagnostic tests.

Later, Watts left the army and worked for the U.S. Navy, where he again worked with Ebola, among other viruses such as the human immunodeficiency virus, or HIV.

“I was looking for Ebola in the South American jungles because why is Ebola in Africa and not in another jungle in other places in the world?” Watts said.

While Watts did not find the answers to his questions, he said Ebola certainly exists in the Philippines

and Indonesia.

“There is an Ebola (strain) in the Philippines and in Indonesia,” Watts said. “This Ebola came to the U.S. in 1989 and visited us in

Reston, (Virginia).”

Currently, there are five documented strains of Ebola–the Ebola, Sudan, Tai Forest, Bundibugyo and Reston.

According to Watts, the Reston Ebola virus was first introduced to the U.S. through monkeys from the Philippines that were delivered to Hazleton Research Products’ Primate Quarantine Unit.

The monkeys were thought to be infected with simian hemorrhagic fever, however, Watts said staff started noticing that the symptoms exhibited by the monkeys were not consistent with that virus, prompting staff to send samples to U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases, a clinical laboratory.

“The monkeys were housed in cages and they were all dying. How does the virus get from cage to cage?” Watts said. “They documented that it was airborne transmission.”

This mutated version of the Reston Ebola was fatal for monkeys, but not for humans.

Watts said the importance of the case was that it showed Ebola could mutate and that it could potentially be airborne.

“My greatest concern, my greatest fear, is that experts are not taking into consideration what is not known,” Watts said. “Certainly, well-documented evidence that the virus spread from monkey to monkey in laboratory experiments does not prove that there is aerosol transmission among infected humans, but it does warrant further studies.”

Regarding the false Ebola scare that recently occurred recently in El Paso, Watts said the chances of someone getting infected are nearly impossible.

“Our chances of becoming infected with this virus are impossible unless we place ourselves at risk by coming into direct contact with an Ebola patient,” Watts said.

While Watts’ research no longer focuses on Ebola, he is currently working on testing a vaccine for a disease that kills livestock in Africa.

Maria Esquinca may be reached at the [email protected].